The title of the new Peter Doig exhibition, ‘No Foreign Lands’, is a bit of a mystery. For most exhibition goers in rainy windswept Edinburgh, the subject of all the pictures on display – that of the Caribbean island of Trinidad – would indeed be highly exotic and intensely foreign. No Foreign Lands is the much trumpeted first major home exhibition for Scottish Doig. But Doig left Edinburgh while still a child, and with his family moved first to Trinidad and then to Canada, where he grew up. The title in fact comes from Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Silverado Squatters, “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveller only who is foreign.”

Like his famous countryman who was also an itinerant and passionate traveller who ended his days in the Samoan island of Vailima, Doig has been resident in West Indian Trinidad for more than a decade now. The place is home. It is only he “who is foreign”.

A painter paints what he sees, either through the sieve of his imagination or directly, from life. And what Doig has seen and rendered onto canvas has been the snow-encrusted mountain slopes, the still fir forests and frozen lakes of Canada with its fleeting passage of skiers and snow boarders, and now for this exhibition, the lush primal jungle, the fluctuating white sands and quavering waters of his adopted Trinidad. It is impossible to avoid comparisons with Gaugin, particularly during the latter’s time in the South Seas – there is the same vibrancy of colour and sensuousness of form. He also shares Van Gogh’s psychological resonance with detail and objects. There are echoes too of Rothko’s profound mystery through form and colour. Doig’s paintings on the surface look disarmingly simple, primitive, the paint applied in sometimes amateurish strokes. But there is something compelling in them. Seen individually they seem thin, but together they gather a cumulative power. A narrative begins to emerge, “I am trying to create something that is questionable, something that is difficult, if not impossible, to put into words.” Doig’s paintings are clearly representational; he is a peddler of mystery too.

This was good news for me. Having been flummoxed in the past by the proliferation of words in some exhibitions, I was seeking an experience that was visually immersive. Looking at paintings is an active pursuit. You have to look with more than just your eyes. You have to engage, have a sort of silent dialogue with the work – “go into it” as I sometimes say. You can’t just flit by as I often see people doing. Of course you can, but you will gain nothing but a superficial reading. A painting will appear a two dimensional stretcher with canvas and flashes of paint, pretty at best.

I decided on an experiment. Rather than go straight to a painting’s blurb as I usually do, I would look at a painting unguided, without rails or assistance as it were, and provide my own story. Looking at paintings is visual, emotional, psychological. Titles are in some ways irrelevant and often the curator’s blurb is a distraction which stands in the way of one’s own understanding.

It was like going on a solitary journey where I was able to see and hear and feel what I wanted to. After “going into” a painting I would steal a look at the description on the wall to see how my “reading” compared. Admittedly, it would occasionally add a dimension that was lacking in my own interpretation. In “Pelican (Stag)” (2004), for instance, of which there are several versions, each giving a slightly different rendering of colour and composition, a dark skinned man in white shorts crosses the centre of the picture. He is on a beach, perhaps on the shores of a lagoon, and is framed by tall palm trees. A flash of light, perhaps the cascades of a waterfall, spill down between the two framing trees, picking out the muscles on his spare frame, casting him in an almost angelic glow. He seems to be carrying something in his right hand. He glances at the viewer, as if he has just turned round, conscious of being watched, but his expression is inscrutable. The meaning is ambiguous, as in many of Doig’s pieces, but the man seems a friendly presence, as though he has emerged revitalised from a swim and is now basking in nature’s rapture. In fact the painting has a rather grisly origin. Whilst walking on the beach with a friend some years back, Doig spotted a man killing something before proceeding to drag it along with him. It was a pelican (echoes of the “Ancient Mariner” perhaps.) The man saw that he was being watched and yelled at the two men aggressively.

In other paintings my own reading was far more interesting than the prosaic reality. In “Mal d’Estomac” (2008) an enormous blue orb rests on a vast red landscape. I saw it as an alien city squatting in the midst of an endless desert, like something out of “Dune”. Disappointingly the blurb informed me that it was a cloud on the sea. Was I wrong? I don’t believe there can be rights or wrongs in interpretation. I’m sure Doig would be delighted. There are no limits to the possibilities of an observer’s imagination working in conjunction with an artist’s, through his work. The painting is simply the beginning of a story that continues every time it is seen. Like the great oral epics, it expands and develops across the years, never quite reaching a conclusion.

There were times though where words failed, where I was unable to articulate in my mind the meaning or story of a work. This was particularly the case in “Balcony (Northcoast)” (2013) – a large canvas in which two hammocks hang empty from inside a veranda. Outside is night, impenetrable, pregnant, concealing something which may be good or bad, or both. The position of the hammocks underlies and intensifies this feeling; one swags in the darkness, the other glows with light from a window. There was meaning in the mood which went beyond words, to a deeper instinctive place where words have little currency. There was story there, I just didn’t have the capacity to pluck it out of the psychological well. I have a feeling this too would have pleased Doig.

“I don’t feel that I have a great deal to say through language. I am not really interested in that form of communication. I communicate through painting.”

It has been said of Doig that his paintings are dream-like. It is true but just as dreams offer many different interpretations, so does his work offer many possibilities. I think the dream quality comes in part from the way the work is derived, which is from photographs. Although his medium is very much paint on canvas, the shadow of the photo seems to be caught in there, conjuring a sort of memory in the observer, a feeling that is both general and specific. There is a sense of déjà vu in encountering his pictures, not so much that one has seen the painting before, but that one has somehow been in it.

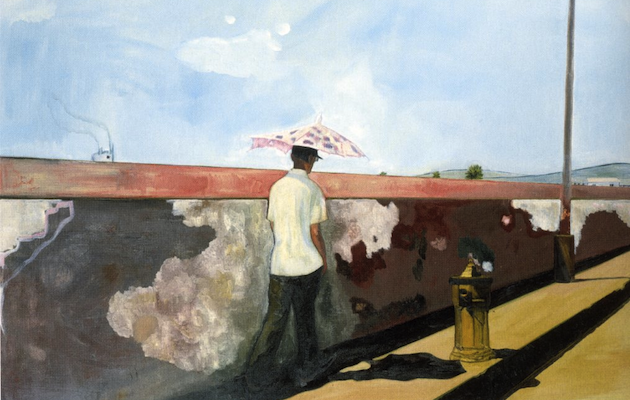

Just as detail in dreams can take on a symbolic significance, so too can the detail in a Doig canvas – often in itself minor and banal – take on a meaning which resonates and transcends itself. In “Lapeyrouse Wall” (2004) a man in a short sleeved white shirt and dark trousers walks away from us along a pavement. To the left of him is a high old patched wall, disappearing from both sides of the picture in classic perspective. A little ahead of him is the stout yellow form of an American-style fire hydrant. Beyond this, to the far right of composition, a tall lamp post is beheaded by the top edge of the canvas. The sky is blue and the three vertical forms of man, fire hydrant and lamp post cast sharp black shadows on the ground. The man holds aloft a slightly broken pink umbrella. The picture immediately prompts questions. What is the wall concealing? Where is the man going? What is he concealing with the slightly furtive stoop of his shoulder? And, really, a pink umbrella? The painting is almost like a scene or shot from a film but whether thriller, drama or comedy is unclear. It is up to us to decide. Perhaps it depends on which dream we’re having.

It is difficult to believe that Doig is of the same generation as middle-aged enfant terribles Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin. But while Hirst seems to have lost his mojo having pickled most varieties of livestock and man-eating fish, and Emin seems increasingly to be found rubbing shoulders with other celebrities on the pages of the glossies, Doig seems content living away from it all, quietly doing his thing. The end of painting has been much discussed and heralded over the past thirty years. On the strength of this exhibition I don’t believe we’re there yet. Far from it.