Larry visits the British Museum’s new exhibition uncovering Egyptian mummies and finds a few intriguing – not to say gruesome – surprises hidden in their wrappings…

You’d think we’d know everything there is to know about the Ancient Egyptians. They were, after all, prolific book-keepers, storytellers and chroniclers, daubing every inch of wall space, tomb space, ornament and sarcophagi casings with images. And ever since we’ve been able to read hieroglyphs, we’ve created a fairly comprehensive picture of life in ancient Egypt…haven’t we?

We are in reality, however, only scratching the surface. Literally. Those hieroglyphs only exist on the surface of things. Tomb finds are rare indeed, and rarer still are those that haven’t been robbed over the ages. And of those artefacts we do have have that contain hidden information, we’re at pains to tamper with them. Open a sarcophagus, for example, and you risk destroying the very material you’re trying to salvage. Until now.

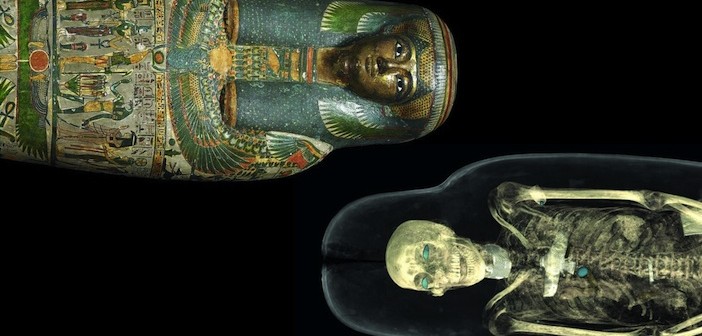

The British Museum’s new exhibition, Ancient Lives, New Discoveries, is exactly that. New technology in CT scanning has allowed scientists and historians to look inside sarcophagi without ever opening them. Scanning mummies is not new, from X-rays in the 1960s to CT scans in the 1990s, but it’s the level of sophistication that has come with recent innovation that has allowed a closer look at what lies within, with unprecedented resolution. And some of the finds have been startling.

The museum’s mummy collection numbers some 120 specimens, of which eight were chosen for the new scientific research. John Taylor, lead curator, describes the idea behind the exhibition, “We’re using cutting edge visualisation technology based on CT scanning to examine the lives and deaths of eight individuals who lived along the Nile between about 3500 BC and about 700 AD. What we’re trying to do here is pick a representative selection from different periods of time and different locations as well as different ranks of society. In addition, we’ve focused on mummies we expected would have interesting facts to reveal. A lot of these mummies have been examined in the past using X-rays but these left a lot of questions unanswered. X-rays would show something under the wrappings but you couldn’t tell what…

The last major exhibition of this kind, Mummy: The Inside Story, focused on one particular mummy when CT scanning had been a novel leap into historical and archaeological research. The results led to the curators creating a 3D film of a journey inside the body. In that exhibition the mummy was displayed with various artefacts and the visualisation was seen in a theatre. This new exhibition places the visualisation and the artefacts in the same space to give the visitor the chance to explore inside the sarcophagi on a personal level, and interactively. As well as the mummies themselves, there are screens with passive reveals of what’s inside but, significantly, some screens have manual controls which allow the visitor to make their own exploration.

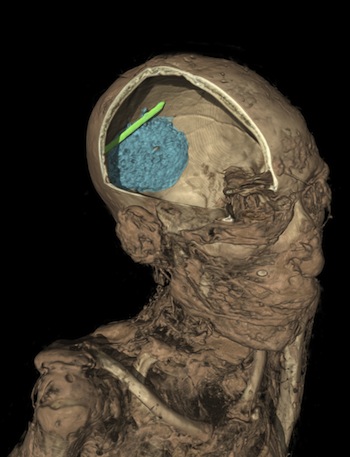

Daniel Antoine, specialist in human remains at the museum, describes the process, “CT scans are made of thousands of slices and what we’ve used are some of the best CT scanners available to generate a huge amount of data which we’ve transformed using some graphic software to represent as close as the science can get us. What is being revealed is incredibly accurate. We’ve also separated the layers, called segmentation, so that these can be revealed aesthetically.” The results are staggering. It’s as if they’ve unwrapped the mummies, without physically doing so. “As you peel away the layers,” Antoine continues, “you get a similar sense of excitement as we did when we discovered these for the first time.”

And some of these revelations are extraordinary, from the gruesome to the ; the remains of a last meal in the stomach cavity of a young man preserved in sand from 3500BC, an embalmer’s tool in the brain cavity of another broken off during the removal of the brain, and amulets folded into the wrappings, shown in such detail that the curators were able to create 3D print-outs to exhibit alongside.

And some of these revelations are extraordinary, from the gruesome to the ; the remains of a last meal in the stomach cavity of a young man preserved in sand from 3500BC, an embalmer’s tool in the brain cavity of another broken off during the removal of the brain, and amulets folded into the wrappings, shown in such detail that the curators were able to create 3D print-outs to exhibit alongside.

The clarity of the finds also prompted a different direction that the exhibition should take, as Taylor explains, “Exhibitions featuring mummies have tended to focus very heavily on death and the rituals of death and beliefs about the afterlife; that, of course, has its place in this exhibition but we particularly want to emphasise the aspect of life, what was the actual experience of living along the Nile all those centuries ago. So we want to use the CT scan data to understand what these people’s lives were like; how long they lived, what they looked like, what kind of state of health were they in, their diet and the illnesses they suffered from. This is where a lot of the surprising discoveries have come, looking at these bodies we’ve found out a lot about the sorts of problems these people had to endure on a daily basis in Ancient Egypt.”

“We’ve discovered a lot about their health,” Antoine continues, “understanding what diseases affected them and finding out about their biology. For example, most of the adult mummies have terrible dental health issues and two of the older mummies have plaque in their arteries, from a diet rich in animal fat. It highlights that these are not new problems; remarkably, here are individuals, several thousands of years old, and they’re suffering from the same ailments as we are today.”

Revelations there may be but there is still much to learn, as John Taylor concludes, “We have not unwrapped mummies in the British Museum for the past 200 years and now curators of today are very grateful to our predecessors for not allowing that unwrapping to take place. Unwrapping mummies is a very destructive process and, as with field archaeology, you destroy the evidence that you want to understand. We’re now very much dedicated to studying mummies non-invasively, to look underneath the wrappings using this technology without disturbing – or destroying – anything. This, of course, is also a more respectful way of treating these individuals. They remain exactly as they were when they were put into the ground. And we hope they’d still be here for scientists to study 200 years from now.”

Ancient Lives, New Discoveries is on now at the British Museum until 30th November 2014. Entry is free to members or £10 for adults, with concessions for students, children and OAPs. For more information, including details and images of the mummies featured, visit the British Museum website.

Ancient Lives, New Discoveries is on now at the British Museum until 30th November 2014. Entry is free to members or £10 for adults, with concessions for students, children and OAPs. For more information, including details and images of the mummies featured, visit the British Museum website.

As well as a fantastic catalogue providing further detailed insights into the exhibition a new book, ‘Regarding the Dead’, has also been produced to coincide with the exhibition, which outlines how the museum curates human remains in its collection, its benefits to our understanding as well as the ethical considerations of studying the dead.