If you think ballet is all about fairies and pink tutus then you should give Mayerling a go. Kenneth Macmillan’s 1978 offering is very much a grown-up ballet, setting itself apart with a male dancer in the lead role and a choice of content, not just shocking in its historical context, but a million miles from fairyland, throwing the Royal Ballet into a frenzy of drugs, prostitution, infidelity and gun-wielding. It is an absolute stunner, pushing the artists to their limits and maintaining a foreboding intensity throughout which races up to the climactic gunshots. It is full of cruelty and depression, sex and death, and this revival at the Royal Opera House lives up to every expectation.

Mayerling © ROH / Bill Cooper, 2009

The Mayerling Incident occurred in 1889 when Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria, heir to the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, killed his young mistress and himself in a suicide pact. Their bodies were found in his hunting lodge in the Vienna Woods and the news critically destabilised the line of succession, heightening the political tensions that led to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and, ultimately, the outbreak of the First World War.

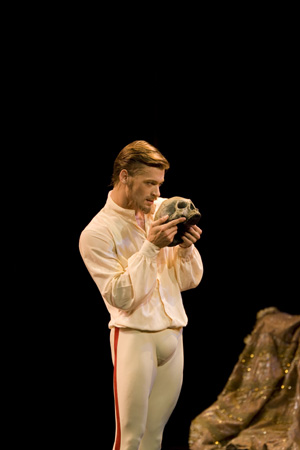

Rudolf is not your average hero, if at all. The curtain opens on the royal celebrations of his marriage to Princess Stephanie, which he spends flirting and dancing with his former mistress rather than paying any attention to her. He is a spoilt prince, addicted to opium, who enjoys a mistress a little too much and is, thus, not immediately loveable. Yet he is clearly a tormented soul, with an obsession with death that gradually consumes him and it is Rupert Pennefather’s portrayal of this – sensitively considered yet brutally honest – that draws you in. It is often said that the role of Rudolf is the balletic equivalent of Hamlet in both its artistic, but mostly its physical difficulty; he is on stage at pretty much all times and has to maneuver seven pas de deux, with five different partners, who he literally has to fling about. It is no wonder that dancers have to take on extra weight training to undertake this part – often quoted as something ‘you wish was over from the very first step’ and that ‘you feel like you’ve done an entire ballet after just one act’, and this man has to get through three of those acts, hurling girls around, managing his solos and still eloquently displaying the pained turmoil of our prince.

Mayerling © ROH / Bill Cooper, 2009

The girls are left with a sprinkling of supporting roles. There are two particular mistresses, a fearsome mother, the beleaguered new bride, and the fated Baroness Mary Vetsera, the 17-year-old who becomes his mistress and agrees to die with him. She was played by the ever-astounding Melissa Hamilton, who brings a force and passion to the part whilst remaining youthful and impulsive. Mary takes a thrill from playing with the gun in Rudolf’s room and jovially picks up the skull that he has agonized over, prancing around with it and perhaps giving him the idea that she might agree to his grave suggestion. She is a girl, yes, but a determined and ardent one at that, and Hamilton sweeps you along in a rush of heady excitement.

This was Hamilton’s first big solo role with the company back in 2009 and, coincidentally, it is her former mentor’s husband, Irek Mukhamedov, who was Macmillan’s Rudolf of choice (and was performing the part in the gala performance during which the choreographer suffered his fatal heart attack in 1992). There seems to be something special about Mary Vetsera and Melissa Hamilton, even if it’s not the biggest role in the repertoire. Her and Pennefather make an electric pair, his internal demons very clearly consuming his every move until it is no surprise to see him as such a wreck, shooting up and staggering about, towards the end. In Pennefather’s hands, the sad demise of the playboy prince is much more touching than it may otherwise be.

Mayerling © ROH / Bill Cooper, 2009

This anguish is assisted by the rich Liszt score, arranged by John Lanchbery and dramatically played under the direction of Martin Yates. The orchestra of the Royal Opera House is joined by a piano in the pit and, at one point a piano and mezzo live on stage too. The music is a wonderful part of this powerful production.

Despite the doom and gloom, the ballet has its lighter moments and it is highly entertaining to see the members of the Royal Ballet in Mayerling’s lavish scenes of debauchery, much aided by the original Georgiadis designs onstage. Girls in the corps do not stand there looking pretty, playing ‘good-toes, naughty-toes’ – they drunkenly loll about, staggering from man to man, drinking, smoking and spreading their legs. There is forever movement in the background, with brawls, falls and clinches every which way, in a somewhat Eastender-ish manner.

The tale is one of two halves, the opulence of the court (with livery and jewels so bright they dazzle you in the opening wedding scene) and the seediness of the taverns that Rudolf so enjoys. It comes as little surprise that the two sides of his life might start to take their toll on him, but to such an extent is another matter. Given that he suggests suicide to a few of his lovers, it seems a fad, an idea of which he should eventually tire, but he is determined and Mary’s infatuation facilitates it, which is grueling to witness.

There is drunken merriment, there is Imperialist pomp, there is manly jostling and there is utterly burning desire, not to mention multiple shootings. Sod the soaps on television – this is what you call proper drama.

For other Royal Ballet productions at the Royal Opera House, visit the website.