With the “Grand Budapest Hotel” director Wes Anderson has scored himself a niche as one of the most singular film-makers working in America. If all the usual Anderson tropes are there – central framing, a striking colour palette, deadpan delivery – then he has also managed to jettison most of the archness and preciousness that accusers have sometimes levelled at his work and has created something very much its own thing, true to itself, and pure storytelling into the bargain. It is perhaps an understatement to describe the film as star studded, the many faces are pressed into the mixture like currants in a giant fruit cake, some so heavily disguised and costumed that it is easy to miss them, but the greatest star is the film itself – a great gaudy show turning brilliantly like one of those miniature mechanical wonders one used to see at seaside resorts.

The film is actually a film within a film within a film within a film, each spiralling backwards but growing in substance and length, like a series of Russian dolls opened from the inside out. First we see a teenage girl tentatively approach the bronze bust of a man set on a high plinth in a cemetery. In the background are squat buildings of a Central European sort and on the ground is snow. On the plinth are hung dozens of keys, the presence of which are obscure although I know that the leaving of such mementoes by pilgrims is sometimes a feature of certain European cultures. Then the girl produces a book entitled “The Grand Budapest Hotel” with the line drawing of a fabulous hotel on its cover.

Suddenly we are transported to a book-lined study where “The Author”, a bearded, woollen-tie wearing Tom Wilkinson tells us that writers do not always sit around making things up, but that sometimes stories come to them. Appetites piqued, we are getting closer to the story itself and we jump back to 1968 where The Author, now a youthful Jude Law, whose dress sense has nevertheless remained the same in the interim (backwards that is) is checking into the Grand Budapest Hotel of the title, a once famous establishment which has seen better days, and better décor. Here he meets the hotel’s owner, the sad and mysterious Zero Moustafa, a purple polo-neck wearing F. Murray Abraham, who offers to recount his story at the place over dinner.

From here we pop back to 1932 and the story proper commences. It is the hotel’s final glory days when Continental aristocrats swish through the gorgeously red-carpeted lobby in fur and astrakhan. Young Zero (played by newcomer Tony Revolori with a literal pencil moustache) has just joined as lobby boy and the whole spanking menagerie is run with a prestidigitator’s finesse by the inimitable Monsieur Gustave (a dazzling Ralph Fiennes) impeccably dressed in purple livery tailcoat, high waisted trousers in dove grey with matching waistcoat, and wing collar.

The device of having a narrator gives it a pleasing “Jackanory” feel, of settling down by the fireside with the intention of hearing a tale by a story telling companion. Yet if you count the Author, young and old, as two separate people, and with old Zero too, there are in fact three narrators, and there is comment here on the way stories are told, how they change as they are passed from mouth to ear, on the nature of story telling itself. There is a sense too that stories become fictionalised in the telling, whatever their provenance, but that truth is not related to fact. It may need repeated tellings to be uncovered. It may even need to be converted into fiction first.

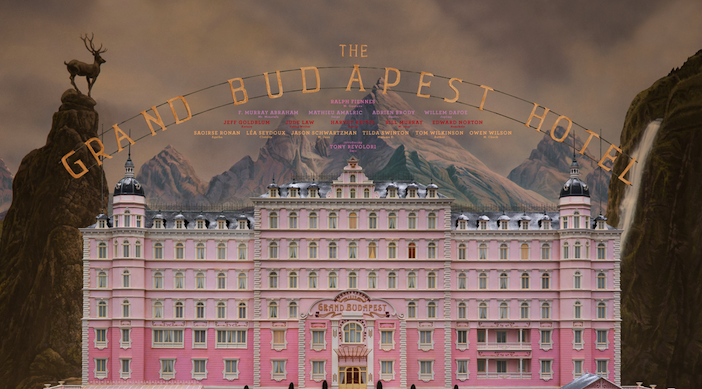

The hotel sits on a mountainside in the Ruritanian state of Zubrowka. This country, alpine in geography, Balkan in flavour, has hints of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire. It is, of course, entirely made up which is perhaps why everyone is speaking English in a variety of accents from Continental (Mathieu Amalric), R.P English (Ralph Fiennes), to Transatlantic, Brooklyn and Texan included! (Harvey Keitel and Owen Wilson respectively). It is a fantasy Europe and yet as in all good parables, is instantly recognisable, more burnished and tangible in some ways than the real thing. And as in the real Europe of the time, war is brewing, the long shadow of fascism, with its “SS” style insignia, creeping across the land and threatening to snuff out the merry, innocent light of “The Grand Budapest”.

The story begins with a zip and verve that never lets up. Ralph Fiennes as the mannered and manicured M. Gustave is seen escorting one of the hotel’s regular clients, the eighty four year old dowager Madame D (Tilda Swinton, unrecognisable beneath layers of makeup) to her waiting car. She is severely troubled, evidently more than usual.

“I love you,” she says to him plaintively as she climbs into the saloon. “And I love you,” he replies without a flicker of hesitation.

Next he is seen interviewing Zero who has egregiously been employed as a lobby boy without his knowledge. Very soon news arrives that Madame D is dead and the two (Zero having been adopted as his master’s gopher)) depart swiftly to pay their respects. At the deceased’s mansion, a variety of grasping relatives have gathered for the reading of the will, headed by the lady’s black-clad and forbidding looking son, Dmitri Desgoffe-und-Taxis (played with spoilt menace by Adrien Brody.) The bulk of the estate is left to him but shockingly for the gathering is that the priceless Renaissance painting, “Boy with Apple” has been left to M. Gustave. Dmitri denounces him as a thief but with the help of Zero he manages to escape with the picture which he locks in the hotel vault. The next day the police arrive and accuse M. Gustave of the murder of Madame D!

And so begins an incident-rich yarn of scheming aristocrats, cold-eyed killers (Willem Dafoe), unbending lawyers (Jeff Goldblum), kindly police commissioners (Edward Norton), prison breakouts, escape across a frozen landscape, intervention by monks, love (in the form of the divine Saoirse Ronan) and restitution of sorts. Ralph Fiennes as M. Gustave, vain but exacting, eloquent and poetic and an incorrigible flirt and seducer of old women, hasn’t been better since he played the Nazi monster Amon Göth in a very different film, “Schindler’s List” (oddly, set in a comparable era.) He is also a decent man and ultimately pays the price for standing up to the jack-booted authority which is then taking Europe by the throat. He and his sidekick Zero, innocent but resolved and adaptable, are the only two characters really fleshed out beyond the bright primary colours of the piece. One doesn’t feel short changed by this. The world is so brilliantly conceived and well drawn that we entirely accept that the villains are in black, the lawyers wear homburg hats and pinstripe suits and the criminals have scars on their faces. We have the emotional touchstones in Gustave and Zero.

I cannot end without saying a word about the design, which in this film is nearly everything. As a production designer myself I am often grieved at how reviewers, keen to demonstrate their knowledge, will mention cinematography, music, editing, even sound design, but will rarely mention production design. In this film it is impossible not to, so striking. colourful and well executed is it. Filmed on location in Germany and at the Studio Babelsberg, with the huge Görlitzer Warenhaus, a defunct pre-war department store, serving as the lobby for the hotel, production designer Adam Stockhausen and costume designer Mileno Canonero have done an extraordinary job in breathing life into Anderson’s vision. Together with extensive use of old fashioned miniatures and matte paintings (the director eschews CGI) an entirely organic and beautiful world has been created.

At its core “The Grand Budapest Hotel”, like most of Anderson’s films, is about family. Zero’s biological one has been killed in his own (fictional) country, Gustave’s is never mentioned and we presume he is on his own; so too with Agatha (Saoirse Ronan). Gustave becomes the unlikely father figure to the young couple. It is this which ultimately gives the film its heart. That a European set and produced period stylised fantasy populated by British, Continental and American stars should be so original and entertaining (let alone work at all) is astonishing enough, that it should be helmed by a native Texan confirms William Goldman’s observation that when it comes to predicting what might succeed in film, “nobody knows anything.”

The Grand Budapest Hotel is currently in cinemas nationwide.