When an earnest, bookish young man travelled all the way to Zurich and met James Joyce, one of the greatest writers not only of his age but of all time, he asked: “May I kiss the hand that wrote Ulysses?”

Joyce, with his quickstep humour that he was known to wield like a broadsword, replied curtly. “No—” he barked, or perhaps mewed in his Irish lilt, “it did lots of other things too.”

Lots of other things, that very hand did indeed do. Ulysses, the mesmerizingly eclectic tale of a day in one Dubliner’s life, is his magnum opus. But Joyce’s powerful impact on the new literature of the twentieth century, and the new nation whose identity he was in no small part responsible for crafting, still is only beginning to be appreciated.

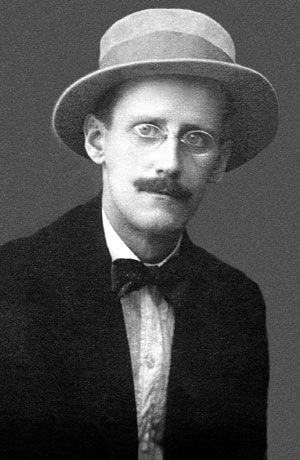

This year, now that seventy years have passed since his death, James Joyce’s work has finally passed out of copyright. For academics, biographers, thinkers of all kinds, it is an opportunity to reconsider an author whose writings have long been known for their sheer inscrutability.

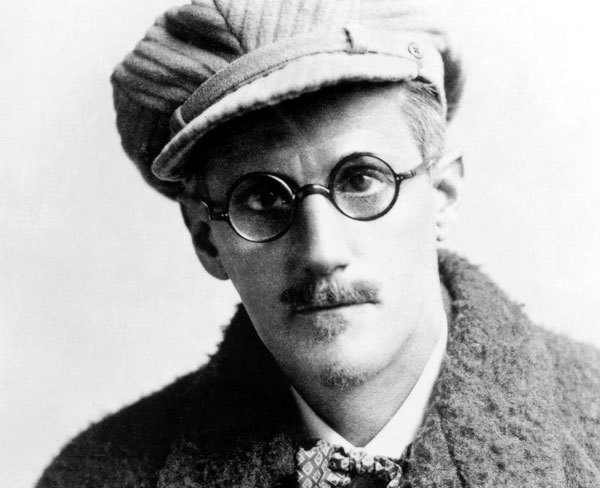

This will of course change little for those long-time admirers who have always appreciated the elegance and the wit, the intelligence and the dirt, and the sheer élan of Ireland’s favourite son. Joyce was born in 1882, in the suburbs of English-ruled Dublin, the city that would provide the inspiration for almost the entire catalogue of his work. Explaining why, he once said: “I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world.”

Yet much of his adult life he spent on the continent, in Italy, Switzerland and France. Nonetheless the Irish still hold him as a national icon: his statue stands on North Earl Street in Dublin, where revellers can momentarily pay him tribute every June 16th, when the city celebrates Bloomsday, the date on which Ulysses is set – before they head off to the ale-houses of the town to celebrate his legacy rather more in the way he would have wanted. Indeed some in Ireland insist on calling Bloomsday ‘Lá Bloom’.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was not his first published work of fiction (that was Dubliners two years earlier in 1914), nor his first attempt at an autobiographical work (albeit in the name of a fictional alter ego Stephen Dedalus). But Joyce’s Portrait attempts something remarkable as he deploys the style of writing and the language of the Young Man at each stage of his growth.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was not his first published work of fiction (that was Dubliners two years earlier in 1914), nor his first attempt at an autobiographical work (albeit in the name of a fictional alter ego Stephen Dedalus). But Joyce’s Portrait attempts something remarkable as he deploys the style of writing and the language of the Young Man at each stage of his growth.

“Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo….” reads the enduring opening line.

The cumulative effect is that through the course of the novel we find more about the developing state of mind of the protagonist, and the effect of his life experiences. Other writers wrote of Portrait in the most praiseworthy tones: fellow Irishman W.B. Yeats called Joyce “a man of genius” and “the most remarkable new talent in Ireland today”; Ezra Pound more pointedly said the book was “damn well written”.

All of this came after the publication of Dubliners, a collection of fifteen short stories driven by a profound sense of purpose. When publishers attempted to alter even the tiniest detail of real Dublin life, Joyce declared: “I seriously believe that you will retard the course of civilisation in Ireland by preventing the Irish people from having one good look at themselves in my nicely polished looking-glass.”

Each of the stories turns on an epiphany, a moment of realisation or awakening when typically the protagonist becomes aware of something previously hidden, previously forgotten: a boy who feels a curious pain at the death of his priest, whilst he sees his family responding superficially; a college student endeavouring to fit in with his wealthy friends but ultimately falling short; a husband who discovers the tragic death of his wife’s youthful sweetheart who died after travelling through the rain and cold to see her when he had fallen sick.

The book is perhaps even an attempt to awaken Ireland to its identity, to its burgeoning sense of self – coming at a time when the movement for Home Rule was growing evermore fierce. The precision with which Joyce wrote about the streets and alleyways, the stations and churches and pubs of Dublin was vital (exactly what he meant when he spoke of holding his “nicely polished looking-glass” up to the Irish people).

A similar awakening was at the heart of Ulysses and of Finnegans Wake, notorious beasts which will go on frightening undergraduates for generations to come, copyrighted or not. Both vast experimental novels, they each take Irish past and present, Irish places and stories, and give them a literary foundation.

A similar awakening was at the heart of Ulysses and of Finnegans Wake, notorious beasts which will go on frightening undergraduates for generations to come, copyrighted or not. Both vast experimental novels, they each take Irish past and present, Irish places and stories, and give them a literary foundation.

Indeed, the very framing of one man’s quotidian story in the structure of Homer’s Odyssey is itself an indication of Joyce’s thinking not only towards the Irish people of whom he wrote but towards man.

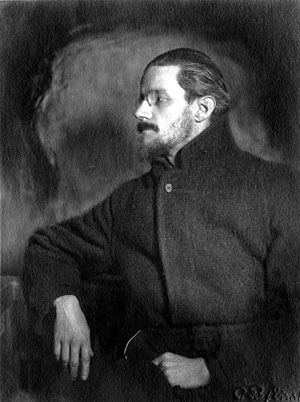

Sylvia Beach, proprietor of Shakespeare and Company, the renowned bookshop in Paris’s Latin Quarter which published Ulysses in 1922, had this to say about Joyce: “He treated people invariably as his equals, whether they were writers, children, waiters, princesses, or charladies. What anybody had to say interested him… Sometimes I would find him waiting for me at the bookshop, listening attentively to a long tale my concierge was telling him…”

That fascination with the seemingly mundane and the ordinary is at the core, the heart which beats through every chapter of Ulysses. Placid, indifferent office man Leopold Bloom is cast as Odysseus; wife Molly as Penelope; Joyce’s alter ego Stephen Dedalus becomes their son Telemachus. The appropriation of a classical, mythological discourse in the ordinary, bluntly humdrum lives of his characters is a Joycean trope: and a manifestation surely of that fascination with human beings, their stories, their lives and loves.

On Joyce himself, Beach wrote that he “fascinated everybody; no one could resist his charm”. The end of the copyright on Joyce’s work opens the way for academics and writers to discuss and dissect his corpus more comprehensively than ever. As his art can now more fully be enjoyed by generations to come, he will continue to fascinate everybody for long to come.