One of the remarkable things about Thomas Mann’s novelle, Death in Venice, is the juxtaposition between the text’s concision and its expansiveness. From what is essentially a semi-biographical postcard, Mann creates an epic which sees the Ancient Gods play with the fortunes of an unfortunate mortal: the writer Gustav von Aschenbach.

This epic is not conventionally Homeric; it is instead an inversion of the Ancient form. The Gods’ actions take place in a dream, the muse is a young, aristocratic Polish boy, and rather than focussing on the heroic deeds of many, Mann’s “Epic” focuses on the salubrious, pederastic indulgences of its single protagonist. Yet the most fascinating thing about this inversion is not its content, but its use of the novelle form.

The novelle is arguably the most German of literary styles, and was incredibly popular among conservative writers and audiences in the mid to late 19th century Germanic world. It is also very short. The effect of placing his “Epic” in a short text, which is generally used by conservative, populist German writers, is almost satirical. What Mann says in Death in Venice, among many other things, is that the idea of telling grand stories about humanity is ludicrous when the individual itself is increasingly insignificant.

Benjamin Britten’s last opera imitates this sentiment. It is an expansive, rich, harrowing opera, but it is also a deathly one. Not only did Britten write it while he was dying, but the strange, atonal longing which the music conveys, suggests an even more profound death, namely, that of art itself.

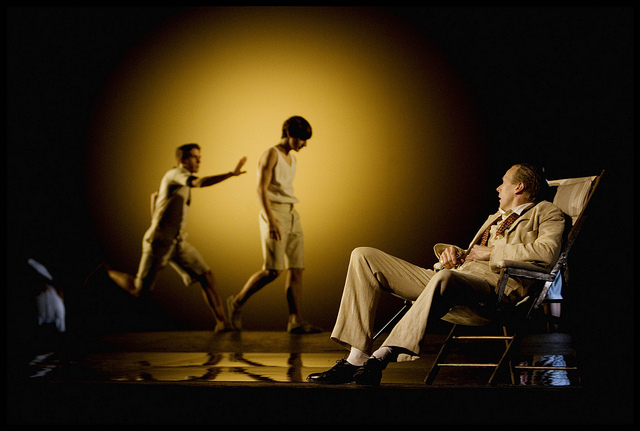

The current revival of Death in Venice at the ENO is a beautiful portrayal of this haunting opera. Deborah Warner’s direction is particularly stunning. The stage highlights the conflict of extremes at work in the music and narrative while also stressing the oneiric landscape of its modernist context. The bold contrast between the alluring back-lighting and the wide, expansive stage is quite breathtaking and the minimalist creation of the Venetian world through large foreign plants and flowing, wraithlike curtains draws the audience, just like Aschenbach, into its exotic, dream-like world.

Aschenbach is played consummately by John Graham-Hall, although at times he does not seem to fully embody the polar extremes of his character. The role is defined by its conflicting desires: on the one hand to be upright, moral, and structured, and on the other to be sybaritic, and unrestrained – the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Yet he never quite portrays the purity of these conflicting natures. The stand-out performance is, however, Andrew Shore whose multiple, symbolic roles are consistently depicted with entertaining brio and deep understanding.

The production is being revived as part of a huge host of events worldwide intended to celebrate Britten’s centenary. Gloriana is being staged at the Royal Opera House at the moment too. But this revival by the ENO achieves much more than a centenary usually does. Rather than simply celebrating the achievement of the composer, this production celebrates Britten’s centenary by holding up a mirror to the world which has passed by over the last 100 years.

When Mann wrote Death in Venice in 1912, art was still clinging on to grand narratives. His work reflects the turning point from the grand to the banal. Britten’s opera also reflects this changed world, perhaps even more sublimely. With its magnificent, ostentatious chords which are dotted with discordant impurities, Britten’s opera questions his form in the same way as Mann does his. Set against the story of the writer who dies dreaming of the beauty of the Ancient World, it straddles the grandiose and the austere, the epic and the real.

Death in Venice runs at the London Coliseum until 26th June 2013. For more information and tickets, visit the website.