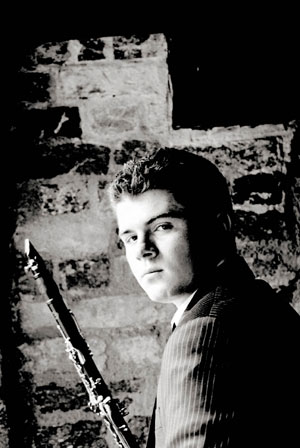

Julian Bliss is surely a case for the progressive education movement, a shining example of nature versus nuture. At the age of five he decided to pick up a clarinet of all things, and learn to play it. His childhood recorder had not hit the spot, a more complex reed was required to blow out the sounds in his head. And so he did, to concert hall standard by the time he was 10, then a spell at the University of Ohio until the age of 12, studying under Howard Klug. Julian, wishing only to play the clarinet, would cut lessons and be found practising in the many rehearsal spaces, devoted to his music. No-one taught him to be this way, neither his mother or father were musical, but supportive when they realised that their son had taken an unusual turn.

Benny Goodman’s childhood was not much different. The child of Polish-Jewish immigrants who settled in Chicago, he was sent to the synagogue to pursue his musical interests. From the age of 10 in 1919 he received two years of classical training and, like Julian, became a strong player, sitting in with bands and learning, soaking up the atmosphere, playing the classical notes so that he could bend them to the prevailing rhythm, jazz, exploding across the nation on tiny discs made from vulcanised rubber, played from large brass horns, firstly in the saloons of the rich, then throughout the world. Sound was born and it changed everything. Enthusiastic dance tunes for a population enjoying the fruits of the stock market boom.

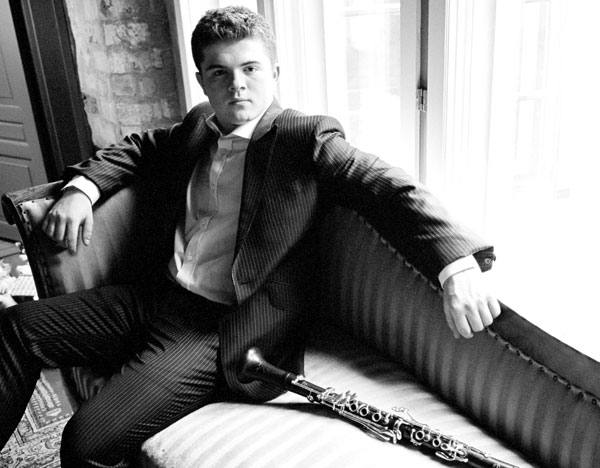

Julian became a classical musician, the highlight of which, he says, was playing for the Queen at her Golden Jubilee in 2002. ‘To walk out on stage to that many people – 12,000 I think it was – in front of the Royal family, and play in their back garden at Buckingham Palace, was surreal, a great privilege.’ I sit in front of this young man in the parlour at The Dean St Townhouse and see someone restless, still searching for the Holy Grail that will define his own musical journey. There is a mercurial element about Julian, at odds with the solidity of his appearance, which is intriguing.

And he’s ready to follow in the footsteps of his idol, Mr Benny Goodman, the bandleader whose skill with the clarinet, whose background in the dance bands of Jazz’s most influential era, is as famed as his attitudes towards discipline.

So when Julian decided to go against the grain and free his playing from its traditional constraints, pages of notes flew up into the air like so many hands, many of them derisive classical critics, questioning the purity of such a decision. After all, he is the young and rising star of the classical world, feted as a genius. Julian seems to accept these nay sayers with a shrug. ‘There will always be those who want me to remain strictly classical, but there is more to my musical ability than just classical music. I love it and there’s no reason I can’t do both.’ His candour is endearing, the fire is under a young man to explore the extensive songbook of his hero. And so he has, releasing his CD ‘A Tribute to Benny Goodman’ made with the septet he put together by word of mouth. In a matter of weeks Neal Thornton (piano) was on board. ‘We spent months listening to every version of each tune we could find, and putting together our own versions while still being mindful of the light and fun feel Goodman captured all those years ago. We then had the task of putting the rest of the band together. We were specifically looking for musicians that had a great interest in the Swing era, and I must say we couldn’t have picked a better set of players.’ Julian’s enthusiasm for his six players is obvious, he seems slightly in awe of the men he leads, the players who follow him, maybe with good reason, because this is a path he has yet to find his feet on. He is as young and bright as the sound of the man he wants to pay tribute to and the recording follows suit; a slightly modernised feel to the original notes may irritate the jazz purists, but this is a requirement for remembrance and the immortality of Benny’s songbook, mere replaying would easily become pastiche and this is, after all, a tribute.

So when Julian decided to go against the grain and free his playing from its traditional constraints, pages of notes flew up into the air like so many hands, many of them derisive classical critics, questioning the purity of such a decision. After all, he is the young and rising star of the classical world, feted as a genius. Julian seems to accept these nay sayers with a shrug. ‘There will always be those who want me to remain strictly classical, but there is more to my musical ability than just classical music. I love it and there’s no reason I can’t do both.’ His candour is endearing, the fire is under a young man to explore the extensive songbook of his hero. And so he has, releasing his CD ‘A Tribute to Benny Goodman’ made with the septet he put together by word of mouth. In a matter of weeks Neal Thornton (piano) was on board. ‘We spent months listening to every version of each tune we could find, and putting together our own versions while still being mindful of the light and fun feel Goodman captured all those years ago. We then had the task of putting the rest of the band together. We were specifically looking for musicians that had a great interest in the Swing era, and I must say we couldn’t have picked a better set of players.’ Julian’s enthusiasm for his six players is obvious, he seems slightly in awe of the men he leads, the players who follow him, maybe with good reason, because this is a path he has yet to find his feet on. He is as young and bright as the sound of the man he wants to pay tribute to and the recording follows suit; a slightly modernised feel to the original notes may irritate the jazz purists, but this is a requirement for remembrance and the immortality of Benny’s songbook, mere replaying would easily become pastiche and this is, after all, a tribute.

Overall the CD is a sunny, genial account of the man and his music. Listening to Julian’s version is a pleasure, but I do miss the crackle of those old vocal booths on ‘Stompin’ at the Savoy’ and the dancehall renditions, when so many would swing to Benny and his inter-racial band (one of the first), are missing from this recording. I think the inclusion of a live version would have been the ultimate compliment to a man who made so many dance the night away. The final mix is a little too clean for my liking and perhaps there should have been an effort to temper the modernity with a more intimate feel, less crisp and more mellow. The ‘Sheik of Araby’, I feel, would have especially benefited, for as beautiful as the flurry of Julian’s clarinet is, it needs a little backbone, a slight heaviness to counteract the reed. These are minor gripes, however, and could easily be remedied the next time around – or with a little less treble on your stereophonic system.

For me, a young classical clarinetist choosing to follow his leader is the natural order of things for a talent who is still green and tender. There is great pleasure listening to Julian talk about Benny Goodman, long dead, with such enthusiasm. “He was just amazing,” he says, leaning into the conversation with excitement, “of course there are the stories about him being tight and demanding with his band, but only because he was driven to be the best. And I think people forget just how good a clarinet player he really was, when you start listening to him you realise how technically amazing he was. And the fact that most of the time he was just playing off the top of his head, but it didn’t sound that way at all.” To listen to Julian talk, clearly forgetting any pre-advised speech, is refreshing, his love for and interest in music is apparent and as yet untainted by what he ought to do. I hope that this CD is perhaps the beginning of a musical odyssey, it may be Benny Goodman now, the obvious choice, but the world has many artists to offer someone with such fire and raw talent. Ali Farka Toure, Toumani himself? Imagine the plaintive clarinet, less often the star player, with such friends to dance around? Benny himself reverted to the classical universe as he grew older, commissioning Bartok’s ‘Contrasts’, at the violinist Joseph Szigeti’s urging, and awakening a new respect for musicians doing things ‘the wrong way round’ so Julian’s aspirations are in good company.

It’s lunchtime now, and Soho is waking up around us. Julian leaves as politely as he arrives, with a shake of the hand and a note to listen to ‘Love Connection’ by Freddie Hubbard. The interview took exactly an hour and whilst I linger on the way out chatting with aquaintances, Julian is long gone to a rehearsal, his fingers itching to play.

Benny Goodman would be proud.

Julian will be playing next on August 18th wearing his classical hat at the Tithe Barn. For details of this and forthcoming shows, please visit his website. For more information about the album and others in the catalogue, visit Signum’s website.

1 Comment

I think the writer is correct, there is certainly more scope for this young artist. Whats next for him?