I’m not cool enough for East London. I always get lost and the shabby-chic trademark of most establishments to the right of Liverpool Street troubles my neat-freak inclinations. Furthermore its artsy inhabitants all too often cause me to curl up with inadequacy, particularly in attire, which screams ‘outsider’ because I’m either ‘Miss Try Hard Verging On Oh So Prim and Proper’ or ‘Miss Hasn’t Tried Hard Enough Because She Doesn’t Have A Teapot On Her Head’. It’s vexing, to say the least. I can therefore imagine many a more enticing prospect than venturing forth into this strange land on a rainy Tuesday afternoon, especially given the post-work promise of dinner and a glass of red at home in the warm and dry. Yet one word had me hurling all caution to the wind and dashing into the hailstorm that had developed outside: Gatsby.

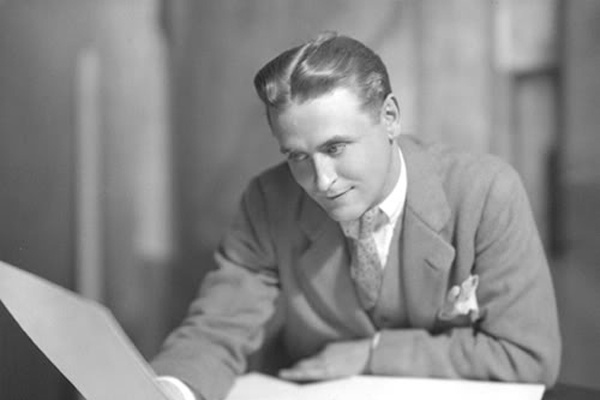

The great, the gorgeous, the simply glorious Gatsby has been brought to life at Wilton’s Music Hall which, for those not in the know, is a theatre-come-bar-come-dance hall dating back to 17-something that is only slightly falling down. Though perhaps an exaggeration, that is only a mild one; Wilton’s has been through the proverbial mill for the past hundred years in various incarnations but is finally being given some TLC and reliving its glory days by doing exactly what it was put there to do. (The tireless team behind it has raised over a million pounds just to keep it upright.) It now provides an interesting new setting for Peter Joucla’s stage version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Twenties masterpiece, The Great Gatsby, and there is a delicious sort of juxtaposition about watching a tale of the idle über-rich on the sunny east coast of America amidst a crumbling old theatre in the grey East End of London.

Right about now you’d be hard-pushed to find anyone not caught up in the glamour and intrigue of Gatsby’s decadent world given the palpable anticipation of Baz Lurhman’s no holds barred take on it. Despite the teasers and trailers and pap shots sneaked from the set, the new film will not grace our screens until Christmas, leaving an unfulfilled yearning to be thrown back into that jazz age. Thank heavens for Wilton’s then! And so to Long Island, where good guy (and the book’s narrator) Nick Carraway has set up home in a bid to settle into business after the war. His next door neighbour is the mysterious Mr Gatsby, who you don’t often see but who nonetheless throws bewilderingly lavish parties week after week, crammed with people who’ve never met him and merely know the notorious name.

Nick’s cousin Daisy lives across the bay with her husband Tom, an old college friend of Nick’s, and as more time is spent with this painfully wealthy couple both we and Nick realise that, in this time of post-war complications and pre-depression tensions, things are not quite as idyllic as they seem. Matters are further complicated when it transpires that Daisy was once in love with Gatsby (that heady, schoolgirl, irrational type of love) but couldn’t marry him due to his unsuitability. Now caged into a miserable yet privileged life with the insensitive-at-best and brutish-at-worst Tom, and a young child, the previously unimaginable reunion is now enabled by Nick. We are thrust into the middle of the triangle when Gatsby and Daisy finally rekindle their relationship, yet we find that she is perhaps not as willing to give everything up for him as he is for her. We also start to wonder how Gatsby came to accumulate all of his sudden wealth; just who is he anyway? This is a tale of glitz and excess, of alcohol and adultery, of longing and true love battling with society’s expectations and undercurrents, with a dash of mystery in between. It is alluringly dark and quite simply addictive.

Nick’s cousin Daisy lives across the bay with her husband Tom, an old college friend of Nick’s, and as more time is spent with this painfully wealthy couple both we and Nick realise that, in this time of post-war complications and pre-depression tensions, things are not quite as idyllic as they seem. Matters are further complicated when it transpires that Daisy was once in love with Gatsby (that heady, schoolgirl, irrational type of love) but couldn’t marry him due to his unsuitability. Now caged into a miserable yet privileged life with the insensitive-at-best and brutish-at-worst Tom, and a young child, the previously unimaginable reunion is now enabled by Nick. We are thrust into the middle of the triangle when Gatsby and Daisy finally rekindle their relationship, yet we find that she is perhaps not as willing to give everything up for him as he is for her. We also start to wonder how Gatsby came to accumulate all of his sudden wealth; just who is he anyway? This is a tale of glitz and excess, of alcohol and adultery, of longing and true love battling with society’s expectations and undercurrents, with a dash of mystery in between. It is alluringly dark and quite simply addictive.

So, trussed up in feathers and pearls with waistlines a few inches lower than normal, my gaggle followed the signs to Wilton’s – “The City’s Hidden Stage” – down assorted alleyways, making our way towards the muffled sound of swing that was leaking from what looked like the tiniest bar we had ever seen. Despite our earliness (which is highly advised), the place was already packed and we could barely see how to shove ourselves through the doors but, dare I say, it really did look like a ‘roaring’ party – you won’t want to stand outside for long (not least for the ‘mobsters’ lingering to sell you French Postcards). Inside, we didn’t know where to look – it was just so damn cool (yet with a drop of nostalgia sufficient to placate any feelings of insecurity within oneself).

All food and drink was Gatsby themed, with Mint Juleps on tap and a rather too delectable Jordan Baker Summer Punch, all served by barmen sporting braces and flatcaps and dodgy Nu Yoik accents. Turns out they were part of the show too as said mobsters brushed past us and took out some glasses on the bar with their violin cases, threatening to take the money out of the bar staff’s wages. They then started a sing-a-long to ‘Blue Skies’ so that the boss could show that he was more than just brawn. The bar doubles as a makeshift restaurant with small plates costing a couple of quid or main meals for a fiver, and all served by some lovely women in aprons. There wasn’t a seat to be had but the growing sense of mutual excitement among the crowd meant that there wasn’t too much jostling and it rather added to the fun anyway. There we stood, sipping our punch through novelty straws, gawping, giggling and squealing at each new bit of the ‘show’ as it emerged, until the time came to queue for our seats.

That’s the one downside of Wilton’s – unreserved seating – which created a slightly on-edge crowd on entering the hall but there was space for everyone and some wonderfully efficient ushers sorting us all out. I think if you book the good seats, you get a table at the front, just like a proper jazz bar (mental note for friends’ birthdays).

Prohibition raid completed, the core cast of eight opened the show by standing centre-stage, singing a capella, wearing huge circular glasses with thick black frames. They all looked a bit strange, I have to say. Yet they weren’t half bad at the singing and as a few flapper-moves crept in, so did the smiles on the audience’s faces. It turns out that the glasses differentiated the actors between their main roles and the background characters, which I thought was going to be confusing but ultimately made brilliant sense. And this singing was the entire soundtrack to the performance, providing incidental music throughout. There were a couple of pitching issues causing moments of disharmony but that’s being picky and, since the actors were moving the set around at the same time, you can hardly blame the odd one for quivering on a note whilst carrying a table.

It was impressive how the production made such good use of its cast given its size. One thing to note here is just how small the whole thing is. I’ve heard it spurned for not creating the right tone through an adequate sense of the massive, crazy parties enjoyed. That’s partly true, I’ll concede – no, you didn’t get the overwhelming impression thrust in front of you that Gatsby’s parties were bigger or more decadent than you could have dreamed. Yet it was alluded to and cleverly so, with use of the audience in the process, which I especially enjoyed because I was taught how to Charleston at the end of the interval. This lack of scale might be considered a downside because it is such an integral part of the original story and a recurring concern of Fiztgerald’s, popping up in his other works as well – the sense that the upper sets of this time were inherently shallow and bored to distraction, thus spurred on to party harder and harder in an attempt at fulfilment without realising that they wouldn’t find what they were looking for by making the gatherings bigger, the drinks stronger or the morals looser.

But perhaps it is a good thing – it’s certainly brave – to strip the story right back and not attempt some half-baked representation of a rip-roaring time. In Joucla’s version, the lack of distraction (noise, crowds, decorations, glitz or excessive showmanship) makes you really listen to the dialogue and really think about the characters – their desires and motivations, their relationships, the impact of their behaviour on others – and those are highly important, poignant themes that Fitzgerald explores too. The fact that the audience is made crucially aware of them is surely a mark of this version’s success and the beauty of theatre is often the slight leap of imagination that is required to fill in the gaps that can’t be physically filled in front of you. Isn’t that half the fun?

As for the script overall, it seemed to flow easily. The dialogue is a little strange and pointed even in the book, yet it was sewn together charmingly here. My purist companion was a tad miffed not to get the well-known opening line but it wasn’t greatly missed since we are shoved into the Buchanans’ world with Nick, making us feel like newcomers alongside him with an awful lot to explore and learn, and there wouldn’t be time for such reflection at the off. Anyhow, we get the famous quote about half-way through at a moment when Nick is surrounded by a whirlwind of insanity and dubious virtue; he seems to be the only one standing still and the words therefore take on extra worth when put into this understandable context, rather than recited out of the blue – say, at the beginning – when they could well sound rather sanctimonious. It’s fine for a narrator with hindsight in the book, not for a lunch guest who hasn’t yet had a chance to get to know anybody in the play, and such adaptation was highly sensitive.

Nick himself seemed a cross between Hugh Grant and last year’s eager winner of The Apprentice. He was slightly geeky and wholesomely upstanding, yet his impatience and increasing irritability with this ‘rotten set’ as he ultimately finds them created a gravitas much needed for the character’s depth. It would be easy for Nick to come across as an affable do-gooder caught like a rabbit in headlights in this frenzied world, possessed of a solid sense of right and wrong but not much wit or oomph. Not so here – he was an excellent anchor for the tale.

Daisy, the famous Daisy, was pretty much as you’d expect her bar the blonde hair (which I’m ashamed to say I missed, even if that’s superficial) but not much more. Most importantly, she was believable, which is the most difficult trait – combining her vulnerability, spontaneity, quirkiness and pain. However, she had a job keeping up with best friend Jordan Baker, the undoubted star of the show played by Vicki Campbell. With a husky voice and easy manner, she possessed an impenetrable sense of self and was utterly beguiling – you just wanted her to keep talking and talking. You see, Jordan’s an odd one. I didn’t much like her in the book – too sure of herself, unhelpful, meddling, a bit prickly, very unpredictable. Yet this Jordan was the girl every other girl wants as her friend and every guy wants as their date – charismatic and utterly entertaining with comic timing down to a tee. Her flowering friendship with Nick had us hooked – they made a naturally hilarious pair – and yet there was still something in her countenance to leave you guessing which side of the fence she sits on – whether she’s one of ‘them’ (the bad lot) or one of ‘us’ (on Nick’s side).

Michael Malarkey’s Gatsby had just the right presence – he could stand there not having said a word and make his authority completely known. What authority this is, who knows, but that’s the allure. Malarkey was tall, dark and handsome, and except for a couple of waverings in accent, sounded not at all bad either (it may even have been intentional – Gatsby could never decide where he was from anyway). Not only did he bare an uncanny resemblance to Ed Westwick (the dastardly heir from Gossip Girl, simultaneously despised and drooled over by teenage girls worldwide) but he was in possession of a steely resolve – a piercing stare and purposive stance – which conveyed passion, intent and a suitable whiff of something sinister without cheapening our hero into a sort of con man.

There were truly giggle-worthy moments interjected with flashes of genuine fear, like when a gun-wielding Wilson rustled through the audience. Tension was carefully crafted, ebbing and flowing where appropriate throughout so that when what we all know is going to happen happened, the gasp in the audience was nonetheless audible and I genuinely felt upset, regardless of any previous knowledge. So that’s my test: I laughed at Fitzgerald’s bizarre lines and wanted to cry at his devastating drama. What is more, despite all the excitement and gaiety (much aided by the Jordan Baker Summer Punch, which I thoroughly recommend), I also left Wilton’s with a deep-seated feeling of sadness at the end, a pessimism or perhaps exasperation at the world and the people in it – what I think is called a heavy heart. And thank Gatsby for that! This is a gem of a book with a profound message at its heart and characters we in turn understand, despise and adore, and this production (every little element of it) did it justice. If and when it comes to Wilton’s again, don’t leave it too late to book your place – you’ll be immersed.

Wilton’s Music Hall, 1 Graces Alley, London E1 8JB. Tel: 020 7702 2789. Website.