Napoleone enters the spacious, sunlit lounge of her white-walled Kensington home for our hour-long interview. We are surrounded by what she terms ‘an invasion of artworks’ on canvas, curled in Perspex, moulded in wax, curved in metal and even lightly coated in cement. Those spanning the floor are cordoned off, an incongruous notion in a family home. An embroidered cat graces Napoleone’s Miu Miu collar, detached from her shirt. In lithe hands she cradles her just-released hardback. Beyond its subtly shimmering, ‘pepperoni’-coloured cover with Pacman font are signatures by some of the 49 contributing women artists given the freedom of ‘no real guidelines’.

“I was afraid to open it at first, but the paper feels warm,” asserts Napoleone, smoothing matt pages gradually. Her Italian accent is refined. “I’ve confidence it will age beautifully, gaining spots of espresso, butter and olive oil,” she adds, drawing my attention to the kerning of the bespoke font used to headline recipes. “The book’s large enough to stay open, and you can read recipes without a magnifying glass. Moreover, at this size images feel like real works.”

This is not a classic cookbook. Images of recipes, including Parmigiano aubergine, artichoke pie and ‘gelato economico’ (easy ice cream), are not necessary, “because people are likely to have seen them before,” says Napoleone. Thus these are vetoed for bespoke contributions and images taken from artists’ archives, which run alongside words by chef Mark Hix and Frieze magazine editor, Jennifer Higgie.

We pause at a monochrome drawing of a single unravelled bucatini strand heading for the pot. It is taken from Aleksandra Mir’s ‘How Not to Cook’, the motto of which is, ‘Sometimes the best way to learn is to make mistakes’. Napoleone explains, “Her book is about failure in the kitchen, while mine is about what to do not to make it a failure!”

Napoleone’s grandmother and mother – living in Verese – and Sardinian mother-in-law contributed recipes, “I remember making mayonnaise as a child,” recalls Napoleone, fondly, “stirring eggs, adding oil, drip-by-drip…” Napoleone is at once pragmatic and philosophical, “Sometimes things went wrong; sometimes the simplest things are the hardest.”

Napoleone calls herself a ‘victim’ of her own obsession with collecting and curating art. The ‘affliction’ began in the late 90s while studying Art Gallery Administration at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT). “There, I met creators and curators, who were also my lecturers.”

One of Napoleone’s first acquisitions was an early work by Joanne Greenbaum. We stand and stare at its bold, colourful lines. “It concerns the imperfection in drawing and sketching; erasing something, adding something new, lightness and mistakes,” she says lyrically. While listening to her appreciation of a creative person’s early endeavours in errors, I wonder whether they mirror her own early years of collecting?

“I would not talk about mistakes,” she responds, “l always end up with pieces that are testimony of a trajectory of my journey as a collector. What happens, instead, is that I feel disappointed when an artist loses motivation. I have wonderful works by artists who stopped and disappeared. What a shame!” She pauses. “Collecting purely for investment is often when mistakes come in.”

Jill Spector, ‘Zabaione Mousse’ (2009) Courtesy the artist and BolteLang, Zurich

A legacy of Napoleone’s time at FIT is that her collection focuses on work by women. “The market was afraid of women slowing down on account of pregnancy and therefore families. But artists aren’t mathematicians!” She traces peaks and troughs in the air, “This is how the graph of an artist goes; a lifetime span. Now, there’s a rush to fill gaps in galleries and museums with work by women, who have always created.”

A graffiti-like fresco dominates another wall. It reads: ‘100% STUPiD’ in girly cursive. “Dutch artist, Lily van der Stokker, who isn’t exactly a young kid in town, combines tough language, which I like, with softening, beautiful colours and shapes.” But what does it mean, I ask? “Obviously it’s a message: either self-reverential, referring to the public for not understanding it, or the very idea of stupidity – ‘what is stupidity, what is intelligent?'”

We segue into the hall. “Sorry for the crates,” she says, tracing fingertips over the biggest cardboard crate bought at London’s Frieze Art Fair. “It’s called ‘Saggy Titties’, by Nicole Eisenman.” A Photostat preview taped to packaging depicts what seems like childish papier-mâché, whereby said ‘titties’ overlap the picture’s boundaries. Offering related intrigue around us are Monika Baer’s depictions of lactating breasts with inset windows opening to roads and brickwork. Napoleone mentions the Baer of today is now more interested in drawing ‘keyholes’.

But dominating the space is a life-size painting of a dancer who committed suicide by Jutta Koether. “I always buy things others don’t want,” Napoleone half-jokes. Grazing on the floor in front of it are enormous wax tongues, the size of a park bench, clasping a martini-like olive. It is a nod to the relationship between art and food realised in Napoleone’s book.

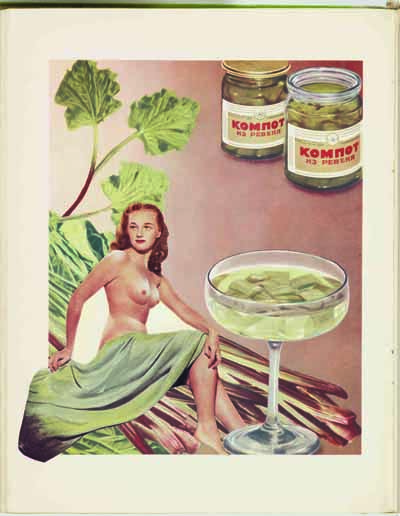

Goshka Macuga, ‘Compote’ (2009) Courtesy the artist and Kate MacGarry, London

Unexpectedly, we continue the tour in Napoleone’s bedroom. She sits on the bed, the best vantage to survey her most treasured works. “Some pieces you never part from,” she says, “they’re like family pictures.”

Rather than the works, I am most intrigued by black ink written notes on lined paper beside Napoleone’s bed. “They’re by my astrologer,” she reveals. “I consult him once a year.” A delicate clock in the corridor by Pae White represents the Aries ram, Napoleone’s star sign.

Above her bed, a portrait canvas, partly covered in solid wash of white and partly dripped upon, is Ghada Amer’s embroidery study of poses from pornography magazines. “Ghada taught me how much I enjoy meeting artists,” she says. I ask her why this is. “I want to live in the reality of time. Contemporary art is different to antiques. It’s all about connections, which is what I try to teach my three children. Contemporary art is about contemporary life. I never buy from artists I don’t know. Artists made their future out of nothing. They found their own way. They didn’t walking the path of other people.” Napoleone lets words breathe. “We want artists to be here in London’s cosmos.”

Considering her clear admiration for, and assistance raising artists, I ask Napoleone a rather obvious question. Is she tempted to try her hand at art? “I never had the desire to make art. My creativity is very much expressed more mentally, curating the collection and curating my engagement within the art world as a patron.”

I set eyes on a folio upon a marble tiled table. It is stuffed with invitations to private views. As one of the contemporary art world’s most prominent collectors, Napoleone is patron of Studio Voltaire, South London Gallery; Chisenhale Gallery and Nottingham Contemporary. She is also on the committee of the annual fundraising gala of the Contemporary Arts Society, and Art Plus Party of the Whitechapel Gallery. And she has judged shows for the Max Mara/Whitechapel Art Prize for Women Artists.

The penultimate room on our tour is the dining room, where a sheer, ominous dark glass flag hangs, high. An artefact-like, verdegris figure of a man by Francis Pritchard glances shyly towards a curvaceous, sassy nude by Lisa Yuskavage. That the figure clasps an erection, slightly furtively, is an unintended but ultimately amusing gesture, says Napoleone.

Linder, ‘Salad’ (1977) Courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art

Finally, we enter Napoleone’s kitchen, the only art-free room in the house. Even the loo features framed sketches of people spied in libraries, one with spiky arm hair. From here, Napoleone caters for 120 artists, designers and curators six times a year. “My pathetic kitchen!” she exclaims. “Incredible. It doesn’t matter what’s at your disposal, but what you do with it,” she adds. It is these, some say, ‘legendary’ banquets of culture and consuming which inspired the three year project that would be Valeria Napoleone’s Catalogue of Exquisite Recipes.

The majority of profits raised from it will be donated to Down Syndrome Education International. Napoleone mentions that Letizia, one of her twins, has seen real results from the practical support the charity provides. “You find a way of understanding how the minds of children with Down Syndrome work – such a different way. But they can learn as much as other people.”

Our hour has become well over two. Napoleone must visit an East London gallery now before returning to collect her children from school. Will there be a sequel to her book, I ask? “Well, I’m still waiting for my mother-in-law to give me her recipe for honey coated Sardinian sebadas,” she smiles, “which aren’t easy to make….”

Valeria Napoleone’s Catalogue of Exquisite Recipes was published on 1st October 2012 and is available at all good bookshops.