September 2nd 1939, Damascus, British Foreign Office

“By night on my bed I sought him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, but I found him not.

I will rise now, and go about the city in the streets, and in the broad ways I will seek him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, but I found him not.

The watchmen that go about the city found me: to whom I said, Saw ye him whom my soul loveth?

It was but a little that I passed from them, but I found him whom my soul loveth: I held him, and would not let him go, until I had brought him into my mother’s house, and into the chamber of her that conceived me.” The Song of Songs – The Book of Soloman

A restlessness pervaded his slightest movements as he sat behind a desk in the small dusty office that overlooked the minarets of the Near East. The call of the muezzin cried and wailed in the distance and each and every object in front of him was heightened with the dry heat from which there was no respite. The fountain pen with which he signed government documents, lay on the blotter, seeping ink into the fibre of the paper and yet he did nothing to stop the flow. He watched the slow, steady progress of the black ink and took a sensuous pleasure in its travels. Dispatches were piled on his desk, which filled his heart with sadness, for he knew that in a matter of days life would change, that this cosseted world couldn’t continue this way. The fan blew stale air around the room and the sun rose to its highest behind him on the balcony. He heard the buzz of an insect in the air around him, the constant clicking of the typewriter outside, the chatter of the secretaries, the creak of the fan overhead.

He pulled at his tie, and, restless, filled with wanderlust, his mind idly considered the evening ahead. Drinks at the club, a formal banquet, talking to people he has no time for, making little distinction between them and those he would call enemies. Perhaps a stolen kiss in the garden with a girl who did not taste quite right, soon forgotten, a night in the arms of a woman, just a body now, not the same in the morning. Breakfast on the terrace with his indifferent, bored wife, recovering from the strength of expensive wines. She would sit reading the papers, her face pale and tired, they lived in the same large house, bound up in regulation social activities, tied to each other, not by love but by convention.

This life here, the life of the privileged British few, shown on newsreels across the world is one that most would envy. But if only those people could understand the facade that keeps it up, one of greed, mendacity, loveless indignity and political intrigue. The traitors that are harboured like snakes in a basket.

The fragrance of the city murmurs to him through the call of the Iman, mint tea, incense, the faint aura of Damask roses, the charcoal of burning braziers, and he is compelled to collect his keys, hat and wallet from their various places and leave the office early. He glances in the mirror as he passes and mops his brow with a cotton handkerchief. If you were to stand behind him you would see him too, blond, tall with a glimpse of eyes as blue as the sea, but weary of the world, the features as definite as a Greek statue, not yet crumbled to dust in the sunset of his thirties. There is elegance in his walk, a certain prowling impatience that belies his need for sincerity from the human race, although he allows others little time to prove themselves. He was a man of first moments, glimpses of desire, of intelligence and sweetness, he looks for beauty inside the dead shells of those around him.

He lives a life of quiet frustration, often anxious and never alone. But who would know as he stands at the head of yet another table, toasts another rowdy evening or takes another girl to bed yet again, that he is always looking for a moment, a feeling, something to jog his memory and his heart out of the stupor it is caught up in? Haunted by recurring dreams, he no longer sleeps, dropping into slumber only to fight battles of endless permutations, he dreams of murders and doing battle with bears, night after night. The local doctor prescribing valerian and teas steeped with the herbs of sweet sleep seem to do nothing for him, for lie awake he does, night after night, dreading and desiring the sopor he craved for peace. But war was imminent, coming closer every day.

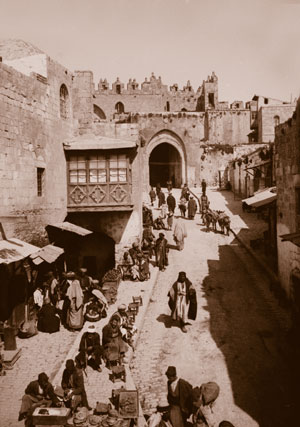

He left the office, said goodbye to the secretaries, put on his hat and walked through the heavy polished doors to the bright sunlight of mid afternoon. Through the gates, past the guards and down the hill lined with high stone walls, covered with Damascus roses, orange blossom and the creeping arms of ancient olive groves which lay beyond and into the old town. Through the market, hordes of children running after him, shopkeepers displaying their wares, the sweet stench of the hookah, the colours of the Near East. The cobalt blue of pure silk rolled out over the blood red of fresh leather, the pure white of the buildings against the sunlight, the folds of the women’s long robes floating around the bazaar, concealing god knows what, or sitting in sequestered windows, gossiping like birds on the wire.

His mind was preoccupied, torn between his duty to do his job, stay at his desk and filter information, and his need, his need to fight and to sign up as soon as war was declared, if not before, to do battle for his country and what he felt was good and true. Dispatches coming through from Europe told him that war would only be days away and yet he had been told, nay commanded, to hold the fort in Damascus instead of signing up immediately to fly in the face of the enemy. The Anglo-Polish alliance was about to be breached, he could feel it, the time to leave this desk bound job and use his skills as a pilot were upon him and yet his hands were tied by convention and the demands of the Foreign Office, the importance of his post, the insistence of his wife, reluctant to relinquish her privileged existence.

He walked until almost dusk, the lamps waiting to be lit in the bazaar, and then realised that he was lost. He had wandered for hours, seeing little, feeling apprehension, foreboding and the changing winds of the times. Irritated, he turned into another alleyway and noticed a bookshop caught between a tea merchants and a rose covered doorway, which no doubt led into an enormous tiled courtyard and scores of rooms filled with women, the thought of which had always fascinated him, these women hidden from view, behind veils. Did they recline on velvet cushions sipping on beverages meant to intoxicate, waiting for their men to come home, so they could stroke them softly with henna stained hands? Did their bracelets tinkle gracefully as they lowered their reddened lips and blackened eyes to the cheeks of their lovers? Who could say, for very few Englishmen had seen behind those tiny doors and discovered the mysteries that were played out in those darkened rooms.

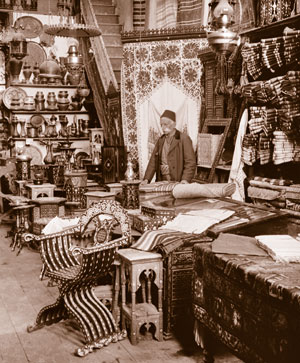

He stood in front of the bookshop window and noted the esoteric books displayed, for which he had little patience, but as he was about to walk away his eye was caught by a slim, leather bound volume entitled ‘Dreams and their Meanings: A Compendium’ and on a whim, which barely left him time to consider his actions he opened the door and walked into the shop, not noticing the closed sign written in French. He heard faint music coming from the back of the shop and followed the noise irrationally to an open door. The small shop was filled with books from floor to ceiling, punctuated by ladders which rose to the heights of learning. He stepped past these and looked through the beads which hung from the backdoor and was suddenly confronted with the interior of one of the very courtyards he had tried to imagine so many times. The fountain trickling in the middle of the azure tiled floor, the old basket chairs, the low brass tables and the ferns hanging from the balconies around. Children shouted somewhere in the distance, the muezzin called the faithful to prayer once again and the smell was of age and some decay, amongst the flowers, the plants and the deep rich scent of cardamom.

He stood in front of the bookshop window and noted the esoteric books displayed, for which he had little patience, but as he was about to walk away his eye was caught by a slim, leather bound volume entitled ‘Dreams and their Meanings: A Compendium’ and on a whim, which barely left him time to consider his actions he opened the door and walked into the shop, not noticing the closed sign written in French. He heard faint music coming from the back of the shop and followed the noise irrationally to an open door. The small shop was filled with books from floor to ceiling, punctuated by ladders which rose to the heights of learning. He stepped past these and looked through the beads which hung from the backdoor and was suddenly confronted with the interior of one of the very courtyards he had tried to imagine so many times. The fountain trickling in the middle of the azure tiled floor, the old basket chairs, the low brass tables and the ferns hanging from the balconies around. Children shouted somewhere in the distance, the muezzin called the faithful to prayer once again and the smell was of age and some decay, amongst the flowers, the plants and the deep rich scent of cardamom.

He moved the beads more to the left and saw a girl sitting on the edge of the fountain bowl, her bare feet in the rushing water, reading a book. Her dark, silky head was bent and she brushed the water up and down her legs idly to cool herself and the sun caught her skin, turning her golden in the dying light. He knew before she even looked up that her eyes would be as dark as coffee, her lips as rosy as the damask flowers which scattered the city with so much grace, that her cheeks would be as soft and smooth as ripe fruit.

He stood in wonderment for a moment, suddenly filled with peace and serenity, feeling desire in his heart. He walked through the beads quietly and saw an old man sleeping in a chair to his right. The girl still did not look up, the noise from the fountain and the quiet jazz drifting from the radio sitting on one of the brass tables must have distracted her. He stood just outside of the doorway and watched her drink tea from a small brass cup, watched her white cotton dress slip from her shoulder and the way she touched her finger to the tip of her nose with thoughtful intent as she read. He waited for something to break the tension now, a movement, a sound that would announce the thumping of his heart to the greater population.

He moved closer until he could almost touch her, and then a grey cat wound its way around his legs and suddenly the spell was broken, she looked up in surprise, dropping the book in the fountain. He took a sharp intake of breath and reached over her to retrieve it from the water quickly, he was so close he could have kissed her and as he pulled the book out he could sense her, above the familiar smell of the city, she was apart from the smoke and the incense, impregnated with the deep scent of vanilla, the night flowers which prospered, creamy and smooth in the gardens high over the ancient city late at night, fed by the starlight. She looked up at him as he now held the dripping book in his hands and her face was as sweet as her smell, rounded and golden lips moulded into a half smile, eyes dark and watchful, welling with tears, she moved forwards slightly as though to touch him, anywhere, somewhere, but she hesitated and took the wet book out of his hands instead. To him she was utterly beautiful. He could find no words for a moment, no reasonable explanation for his presence, though just moments before, it had all been so clear. He had wanted to buy a book. She stared at him questioning his appearance in this inner sanctum of the house. He took off his hat.

“I’m sorry to disturb you. I wanted to buy the book in the window, the one about dreams. I have this recurring dream you see and I wanted to know, what it means.”

“What do you dream?” Her voice was soft and hesitant. She stood up, embarrassed and adjusted her dress, dabbed away the tears.

“I dream of fighting with bears, of battles and bloodshed, night after night.” He wanted to take his fingers to her face and wipe away the tears under her eyes, stroke her golden skin.

She sighed and walked over to the old man, woke him gently, poured him tea, propped up the pillows behind him. He awoke with a start and looked curiously at the young man in front of him. The girl whispered something to him and then turned around.

“Speak to my grandfather. He knows about these things more than I do. But he is frightened, we listen to the news, war is coming.”

“Speak to my grandfather. He knows about these things more than I do. But he is frightened, we listen to the news, war is coming.”

“I know.”

She pushed her feet into leather slippers and disappeared through the beaded curtain whilst the old man sipped his tea and beckoned him closer. The newspaper lay at his side, the headlines filled with doom, the storm was about to break. His old, gnarled hands gripped his stick and as he spoke it was the speech of an Englishman, tanned to leather after years in the east. Youth next to age.

“So you dream of fighting, of bears and wild animals?”

“Yes.”

“You want to fight, you cannot in your waking life, so your dreams are filled with the sounds of battle. You have something to prove to yourself or to the world young man.”

“I suppose I do. I feel frustrated by what I cannot do. I want to do something worthy of my life even if I die in the process, as long as I am worthy. I have nothing to live for.”

“There is nothing yet, but that will come, it always does, when you least expect it. Now, I must close the shop properly and eat dinner, you are welcome to join us.”

The old man looked at him keenly, standing there with his hat in his hands and saw the war in his mind, clearly written on his face. A life, as yet, untouched by love or glory, searching for destiny.

“I can’t sir I’m afraid.”