He thought of the banquet and longed to be here, in this courtyard, to see the girl again, to listen to the wisdom of the old man, but he had to do his duty. He took his leave of the old gentlemen and walked back through the curtain and into the shop. The girl stood beside the door, holding the book from the window in her hands. He knew that he must see her again, as soon as he could, that he would know no peace until she was in his arms. She looked up at him with longing in her eyes. He tried to pay her for the book but she shook her head and he left the shop, closing the door behind him, she, fastening the shutters, leaving him wondering if it had all been a dream, conjured by the lamplight.

He looked at his watch and hurried along the alley, noting the street name beside it and an hour later managed to find his way out of the maze. She stood and watched him leave, her head leant against the glass. She was short of breath and knew that the arrival of this stranger had changed her life forever. They had met before in a thousand dreams and she had seen him in the hands that passed her morning coffee, sparks of passion from restaurants and gardens, sometimes on the tram, flashes of the pleasures to come, always fleeting, never quite complete. She had been looking for the race that knows Joseph in all the wrong places, until now and he had found her, when her loneliness and desire for love had finally overwhelmed her with bitter tears in the late afternoon.

That night he stood in front of the mirror in his bedroom, attempting to knot his bow-tie. His hands were unsteady, maybe from the whisky, perhaps because of the girl. He brushed his hair with the silver brush on the dressing table and plenty of royal yacht lotion, looking every inch the gentleman that he was. The seething and passions lay well hidden under the cold, calm exterior he presented to the world. The book of dreams lay on the table and he opened it idly, flicking through the pages as he sat down to have a last cigarette before he left. One of the pages caught and he found a note. He closed his eyes before he read it, knowing almost what it might say, hoping against hope.

When I saw you today, I could not explain my need to touch you, to kiss you. If you find this note what I desire from you is meant to be and you will find me tonight on Formosa St. and I will know what it is for you to hold me in your arms. I don’t know what is right or wrong any longer only that I need you here, with me, tonight. I will leave the lamp burning in my window.

He folded the note in his pocket and finished his cigarette. He knew that he would go, no matter what.

He could hear music coming from the gardens in the consulate and he wished that he was far, far away, in her arms, breathing her. Later on he danced and drank and ate, laughed with those who called themselves friends and held perfumed, powdered women as he danced, but nothing gave him the sense of peace and serenity he had felt earlier, just standing in front of the girl from the bookshop. He seemed separate and distanced from his wife, elegant, she stood amongst a throng of women, laughing and smoking and he tried to remember a time when he had loved her, when she had given him peace, and failed. The men spoke of the war in tones of reverence, yet none of them seemed as ready to fight as he was. They seemed content to stay where they were, protected and living easy lives. His wife walked past him, a stranger to him for years, she did not turn to look at him or brush his arm as she passed, he was as invisible to her as she had become to him. It was as though his whole life had been based on a foundation of shifting sands, populated by the ghosts of what might have been. He thought of the war, moments away, he thought of the girl and knew how she must taste, sweet and dark, her smell of flowers and almond trees, the vanilla of her skin, so different from the other women around him, who tasted bitter to his tongue, his senses. He left glasses of champagne half finished, conversations hanging, smoked cigarette after cigarette and drank neat whisky until neither his calm or his cool was apparent and he left the grounds of the consulate, walking down the hill again and into the old town.

He could hear music coming from the gardens in the consulate and he wished that he was far, far away, in her arms, breathing her. Later on he danced and drank and ate, laughed with those who called themselves friends and held perfumed, powdered women as he danced, but nothing gave him the sense of peace and serenity he had felt earlier, just standing in front of the girl from the bookshop. He seemed separate and distanced from his wife, elegant, she stood amongst a throng of women, laughing and smoking and he tried to remember a time when he had loved her, when she had given him peace, and failed. The men spoke of the war in tones of reverence, yet none of them seemed as ready to fight as he was. They seemed content to stay where they were, protected and living easy lives. His wife walked past him, a stranger to him for years, she did not turn to look at him or brush his arm as she passed, he was as invisible to her as she had become to him. It was as though his whole life had been based on a foundation of shifting sands, populated by the ghosts of what might have been. He thought of the war, moments away, he thought of the girl and knew how she must taste, sweet and dark, her smell of flowers and almond trees, the vanilla of her skin, so different from the other women around him, who tasted bitter to his tongue, his senses. He left glasses of champagne half finished, conversations hanging, smoked cigarette after cigarette and drank neat whisky until neither his calm or his cool was apparent and he left the grounds of the consulate, walking down the hill again and into the old town.

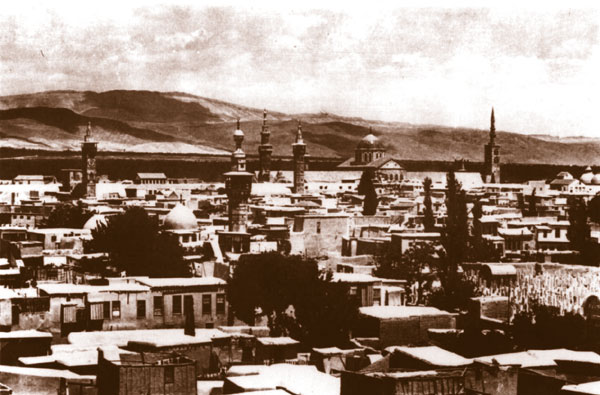

As he walked he sobered up and found a child to show him the way to Formosa Street for a farthing. The market was still, lit by lamps and the smell of food and spices was overwhelming. The moon hung low and golden as he finally approached the front of the bookshop, closed. Lamps, dotted around the tea merchants next door illuminated the street and he could see no sign of the girl or her grandfather, only a young man behind the old fashioned counter, weighing up teas and spices for his customers. The rose covered door to the courtyard was firmly shut. He looked up to a window above the shop and saw, as promised, the light burning behind the shutters at the very top of the house, seeping into the street. Wandering what to do he picked up a handful of dust and threw it at the window, out of the eye line of the boy behind the counter. After a moment the shutters opened slowly and a key was thrown out. He picked it up from the street and stood for some minutes, examining it. There was still time for him to go back to the consulate, to reinstate his former life, to continue in safety, but that seemed impossible. His deepest desires had been answered finally this afternoon and few questions remained in his head. He had as surely left behind mendacity and duty as prescribed by others in the garden of the consulate as he had found some purpose in the eyes of the girl on Formosa Street.

He unlocked the heavy door to the hidden courtyard, closed it behind him and found himself walking along the tiled corridor, heavy with its remembered scents of the afternoon, only heightened now by the moonlight and the bloom of the orange trees. There was a slight rustle and she was there, in his arms, standing on her tiptoes to reach up to him. He picked her up and found her lips against his own and she tasted sweet, like honey, like the flowers of the east, the taste of home, the sun on his skin. She was all of these things at once, her arms were now his home, no matter that they had barely spoken, that there were undoubtedly insurmountable problems, what did it matter, here and now, in the still of the night? A song ran through the air as she led him through the courtyard and into the shadows, up staircases and into the roof of the building, protected by a wooden, screened palanquin, where the air was cool and the stars shone over them.

He sat down on a chair in front of the bed and she stood in front of him. He buried his face in the flesh of her rounded belly, felt the soft skin between her thighs and pulled off her dress, until she was left with just her silk shawl around her. She lay down on the bed, curled up, and he walked around her, only taking off his tie, the black dinner jacket, the starched shirt front, slowly deliberately. She held out her arm for his body and he sat beside her in the moonlight, stroking her, kissing her here and there, mapping out her body with his eyes and hands. Then his face was buried in her silky hair, his fingers caressing her neck and below now, breasts, collarbone. Gently, so gently for the merest moment, then he tugged her hair back suddenly and kissed her face whilst murmuring endearments, provocations, the like of which she had never heard outside of her mind before, but which spurred her to answer back for the first time, those words, tangled and twisted in her head for months. The mere scent of him was right for her, beautiful grassy and fresh so she buried her face in his skin and saw the difference between her dark locks and his golden hair. Her body was perfect for him, they fitted together like warp and weft, she small, soft and rounded against the long, agile angles of his body.

Much later on, lying next to her in bed, he heard the call of the dawn muezzin, the chirping of the grasshoppers and the rush of wind from the desert. His mind was filled with happiness suddenly, his heart was free. He whispered her name over and again, Aurora, Aurora, the evening star, the dawn of his new possibilities, of a life lived anew. And then he allowed his discipline to finally break and it felt as though years of indifference and indecision had been washed away and there was suddenly only this pure sense of purpose, of being alive, being true to oneself, no matter the consequence. They slept later and he did not dream of fighting for the first time in years, but of the sea, at home in England, of the warmth of his mother’s embrace, the smoke of his father’s pipe, the soft grass of Devon underfoot, the laughter of his own children not yet born, the smell of his home in the country, the bark of the dog when the church bells rang and the sweet gloom, golden as only England could be in the summer. The hum of bees in the herb garden, a silver teaspoon against a china cup, the snow of midwinter, the crackle of the fire. Home. He had finally come home. He slept with his arms around her belly, soft and slack with sleep and something else drifted over them too, not easily defined, but that night they had created life and soon she would carry living proof in her belly of his love for her, as innocent as only true love can be, yet filled with the complexities of passion and their darkest desires.

They awoke to the sound of the radio at dawn and the voice of King George, announcing that England was at war, followed by an address to the country by Winston Churchill and he knew then what he must do. He spoke to her of his conflicting duties at length, of his desire to be of service. They spoke of their own problems, fresh in the dawn, his wife and the joyless life they led, the ignorance of race for Aurora was part Arab and life would not necessarily be easy for them. She spoke of her grandfather and his continuing frailty and the difficulties they might face.

“I must sign up you see. I must do something more to help, and I can.”

“You must do what you think is right. But I cannot lose you so soon.”

“You can’t lose me, I’m yours now my darling. I love you.”

At 8am he arose and kissed her, leaving his signet ring on her finger, tasting her tears and promising to come back later, he crept down the stairs, through the courtyard and into the street, leaving the house on Formosa Street and his love behind. He walked through the waking bazaar with a smile on his face, of contentment and peace, he could smell her all over his skin, still sweet. He had to defend his love and the country he loved so well, not only for himself but for the future. After some thought he walked through the haze of the morning to his club where he washed, shaved and sat down in the drawing room to write four letters, one to his mother in England and the old man on Formosa Street, explaining his intentions, the third to the Foreign Office, tendering his resignation, effective immediately and the final one to his wife at the Consulate. He gave the letters to a servant to deliver and walked out again into the sunshine, seeing the ancient city as he never had before, ablaze with sun and happiness. He bought fruit from a stall, drank tea at one of the many roadside cafes, smoked a hookah and watched his fellow men ebb and flow with life in front of him and for the first time in nearly forty years of life he was at last, himself.

He walked back up the hill, past the old office that he had left for the last time yesterday afternoon, so torn in spirit. He passed the consulate compound to RAF headquarters where he signed on to fight and was accepted as an Officer. He never went back to the large house on the hill in Damascus or to the life and marriage which had left him cold for so long. He went home to the courtyard on Formosa Street, where he lived until he was posted back to England.

He lived to see the birth of his son in June 1940, and his daughter in April 1941.

The last time he saw Aurora was in the cockpit of his Lancaster as it went down over Normandy in January 1942. He had been flying for many hours, his long legs cramped in front of him as he ducked and dived mistakenly out of formation and was hit from under the fuselage by a German sniper. He knew that it wouldn’t be long as the plane began to smoke and the rattling and screaming from the back grew louder and the sudden searing pain in his legs almost blacked him out. The engines behind and above him were deafening, there was no escape. He looked behind him and saw his navigator slumped over the dials, his face bleeding. And then it all seemed to be no more and there she was, smiling at him, her hand in his and his ring on her finger, given to her that morning in Damascus, no need for a marriage certificate, theirs was a spiritual bond, stronger than a mere slip of watermarked paper. Memories of her washed over him like a healing balm, the contented sighs she made in the morning, the way she whispered his name as they made love, the sound of her laughter, the rushing of the fountain in the courtyard, the smell of Damascus and her skin. The mother of his children and the love of his life, they had been given so little time together, but he had found her and his life had not been in vain, for her or for the freedom that he so believed in.

He closed his eyes and found the light.

In loving memory of Flying Officer Edgar Prytherch-Lloyd, Flying Officer Gerald Mildmay Blundell-White, and all the other brave men who fought in WW2.