Henry Bird stood on the front step of his house. His hand still held the key in the lock of the front door. He always shut the door with the key, turning it in the lock to avoid that bang which set his teeth on edge. He had repeatedly asked his wife and children to shut the door like this but they thought he was being precious and pernickety. There was no bang, or if there was, no worse than passing traffic of the neighbour’s T.V. Bangs were a part of life – you had to learn to live with them. Inevitably there were arguments. Sometimes after careful reasoning (or more often than not, pleading) they would comply with his wishes. But they soon forgot and he gave up complaining. He never, though, stopped shutting the door in the way he wanted it shut. There was principle as well as reason for it. Even if everyone in the world was banging shut their doors, he would continue to close his quietly with a key. Perhaps in time they would learn.

He continued standing there for some moments, one hand on the key, the other on the central doorknob, brow furrowed. He didn’t feel right today and he couldn’t remember why. He wound fuzzily through a mental checklist. Angina, arthritis, the sun spot on his head and the new pain that had developed behind his knee – all these were intact and continued much as they had before, inconveniencing him, making him feel old and forming the source of regular health bulletins to his wife. Then there was family. But family was always a worry. His finances were stable but continued to trickle away against his investments now that he was retired. All these were as before. So what was it?

He continued standing there for some moments, one hand on the key, the other on the central doorknob, brow furrowed. He didn’t feel right today and he couldn’t remember why. He wound fuzzily through a mental checklist. Angina, arthritis, the sun spot on his head and the new pain that had developed behind his knee – all these were intact and continued much as they had before, inconveniencing him, making him feel old and forming the source of regular health bulletins to his wife. Then there was family. But family was always a worry. His finances were stable but continued to trickle away against his investments now that he was retired. All these were as before. So what was it?

He considered opening the door again. He hadn’t called out to say goodbye to his wife as he usually did when leaving the house. But he had already shut the door. Opening it again would feel like repeating something, turning back the clock. It felt like a waste. Then a little spiteful sensation twitched in his mind. He would withhold his goodbye from his wife. This gave him pleasure. Then he checked himself. Where did this thought come from and why did it please him? Had his wife hurt him? Why did he want to punish her? He wrestled with these thoughts for a few minutes but made no headway. His mind felt soft and heavy, obscured. Is this what senility would feel like, he wondered, groping but never finding? He hoped to God that this wasn’t what it was. He could cope with the physical infirmities, but losing his mind, becoming a cabbage?

By this stage Henry Bird had forgotten all about his wife and the withheld goodbye. He was climbing down the steps into the autumn sunlight, moving out of the shadows of the big Victorian house that had been their home for more than thirty years. He was going for one of his regular afternoon walks and he was hoping that the activity and fresh air would help shift some of this stubborn clay that clung to his mind.

“The soil of the streets, Henry,” his father used to say to him, “is where you’ll find the answers. There’s no problem, however big, that can’t be worked out on a walk.”

He smiled into the sun. He already felt better. He rolled his shoulders to adjust the hang of his overcoat. It was too warm for it really – a pullover would have been sufficient. There weren’t many days in Sydney when an overcoat was needed, and his wasn’t merely wool but cashmere. Still he liked to wear it when the weather turned. He had had it cut on Saville Row in the Sixties when he had lived in London for a few years. There had been little call to wear in since his return but on a whim he had begun to again on these winter walks. It lent them a sort of occasion. He found himself walking tall.

He ambled past the flower shop and new café, which also doubled as a delicatessen. They had started buying their bread from here. He turned and caught sight of his reflection in the window. For a moment he thought he was looking at a stranger. Who was that old man looking back at him? He rolled his shoulders again and lifted his chin. But it was no good. If anything it made him seem a little absurd. And his stride was no longer a stride. It was more of a deliberate shuffle. Although he had recently turned eighty, he still thought of himself as a young man. Inside he felt forty or fifty. He was at his peak. When people were overly reverential towards him he felt like remonstrating and saying “There’s no need for that. I’m just like you! Be breezy! Share a joke with me!”

It was worse though when they stared right through him, as though he wasn’t there. Particularly the young women. He would feel himself diminish slightly, disappear into himself. His aches and pains would return. He would feel old.

It was worse though when they stared right through him, as though he wasn’t there. Particularly the young women. He would feel himself diminish slightly, disappear into himself. His aches and pains would return. He would feel old.

He reached the end of the street. A big old Jacaranda tree stood proud above a fence and spread its arms across the pavement. A few wilting blooms still clung to the branches. In spring and early summer it was a riot of colour. Good old tree!

He crossed the road. A car screeched out of nowhere. He had to break into a hobbling run for the last few paces. The car whined past. He had worked in a fast profession in his time. He had known sleepless nights and tight deadlines, frantic telephone conversations. He knew what it was like to be up against it and to be battling against the shifting hands of time. On one big, crazy contract he drank nothing but coffee for three days. He didn’t sleep a wink until the proposal was received by the clients. But there was reason for all this. These days things seemed to be getting faster without purpose. It was speed for speed’s sake. Like that car. Why was it in such a hurry? To get tot he bottle shop five minutes before it could have got there? For what? For five extra minutes of drinking time?

Henry Bird caught himself. He knew this where this was going. He had enough self-awareness to realise that it may have been him that had slowed. It just didn’t seem that way. He felt constant. The sun rose and set, but it was the earth that moved… He knew what he meant. He smiled bleakly to himself.

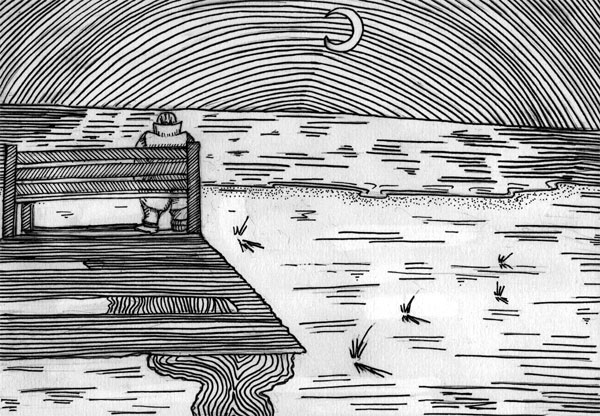

He could see the trees of the park now and beyond, the ruffled waters of the harbour – there was a wind blowing out there. This was his destination. He would take two turns, walking beneath the tall Eucalyptuses of the perimeter, skirting the muddy sandbank of the shore inlet before climbing to find his bench, always the same one. Here he would take out a book and read, or more often than not sit, and watch, and breathe.

He entered through the gates. The cries of children echoed up from the shore. There were a couple of nine or ten year olds there, scampering about with buckets and sticks. Hunting for crabs probably. On one side a mother walked slowly with a pram and toddler. In the middle someone was booting a ball. They were all in the distance separated by space and thought. He was glad. His park walks were solitary time, away from family, wife, neighbours, sometimes if he was lucky, away from himself.

As he walked he found his earlier questions dim and fall away. Left on it’s own, and more prominent because of this, was that first question that had bothered him on the steps. The trouble was, now as then, he couldn’t quite discover what this was. He knew it was significant because it remained, seemingly immovable. But it was shrouded, opaque. It was frustrating. It was like having an important word on the tip of your tongue.