Bullets were flying. Fires were raging. Buildings were falling. Leaders had been toppled, cities had been ravaged and entire countries had been divided. Those who chose to remain in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt in the Arab Spring of 2011 barely ventured out at night, while thousands left altogether – not least the numerous tourism agencies operating within the tumultuous three countries. One lone Westerner, however, made the emboldened decision to travel there, and experience the Arab Spring revolutions as a tourist.

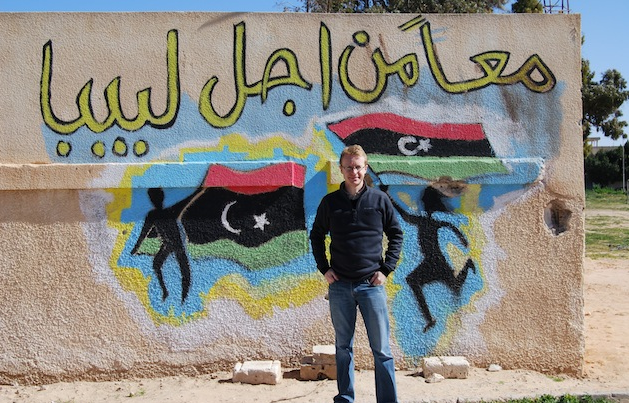

The Times travel writer Tom Chesshyre is endearing in that he doesn’t set himself up as a hardcore foreign correspondent, and in his new book, A Tourist in the Arab Spring, he recounts his explorations through Tunisia, Libya and Egypt as a lay traveller. “I’m not Jeremy Bowen and I’m not an expert in the Middle East and that’s what I tried to bring to the journey – I was trying to understand it without any preconceived notions”.

Inspired by the “idea of revolution” and previous landmark upheavals such as the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Cold War, Chesshyre sensed that “this was another of those moments” and booked himself a flight to Tunisia, where the Arab Spring began with a fruit seller self-immolating in protest at the country’s corruption and working conditions. “When Gaddafi fell in October 2011 I looked at the map and realised, ‘Hold on a minute, there’s a whole line across the top of North Africa where these countries are overthrowing their dictators’. I booked a £65 flight to Tunis and travelled across from there”.

Throughout A Tourist in the Arab Spring Chesshyre really does set out to visit the traditional tourist attractions including Islamic cultural capital Kairouan in Tunisia, Libya’s Roman ruins and the treasures of the pharaohs in Egypt, but what is insightful is their juxtaposition with the cigarette smugglers, bullet miners and characters of a shady disposition that often court a country in tumult.

In unembellished yet vivid prose, we see through Chesshyre’s eyes an aberrant world in which its new identity hangs in the ether, such as in his drive across Tunisia, where ‘the landscape opened up, the horizon spreading ahead. Great grey clouds billowed towards the heavens, as though the end of the world was nigh… Then there were cacti…thousands upon thousands of cacti. The highway rolled towards Hammamet, the beach resort: not a single tourist coach in sight.’

The unease and alienation experienced by Chesshyre throughout his journey is often anchored by bathos, however, such as when he is the sole customer in a deserted restaurant being served by a bewildered waiter, or is informed that the sound of fireworks he falls asleep to every night in Libya is actually “happy shooting”.

What is obvious throughout the book is how Chesshyre is struck by the affability and openness of the people he meets. “In all the countries, but particularly in Libya, people hadn’t been able to talk to others about their lives for years. Under Gaddafi, they were too afraid of being recriminated, so it was remarkable actually hearing people telling their tales and what happened to their lives – what had happened to a brother, or someone who had disappeared and turned up four years later because police had picked up the wrong man”.

Three weeks after Chesshyre left Libya, the US Ambassador to the country was killed by terrorists, and Chesshyre is unequivocal that should the events which succeeded his journey have occurred beforehand, he would not have visited Libya – not least because he was hijacked there. “My driver and I were travelling to Benghazi, and at the first checkpoint the guards were very unfriendly towards us and were suspicious of me from the start. The driver didn’t have the correct paperwork, and while they had him out of the car others got in, started the ignition and simply drove me away at 150km per hour into the desert.”

Being tossed around on the back seat entirely on his own, Chesshyre recounts how he “suddenly realised I was really at risk and I thought how much of a stupid idiot I’d been. I was really worried”. Fortunately, he and his driver were separately taken to a brigade headquarters, and managed to “talk our way out of it”, but he still regards Benghazi as a “threatening” city.

Another of Chesshyre’s travel titles includes To Hull and Back: On Holiday in Unsung Britain. Is it possible that as with A Tourist in the Arab Spring he’s not a tourist at all, but a traveller desperate to eke out something unsung, unseen and find the insuperable road less travelled? “There aren’t many adventures left in the world, and travelling across Tunisia, Egypt and Libya as a tourist gave a sense of focus to the adventure. Travellers will always want to visit the unsung and the ‘anti-tourist’ destinations because the whole world is covered now, everyone has gone everywhere. It’s not easy to find somewhere that hasn’t already been covered, so I’m interested in seeing the overlooked places”.

The Arab Spring itself could engender new tourist attractions and historical landmarks, from Gaddafi’s burned-out bunker to Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s deserted palace, but Chesshyre is circumspect in predicting the tourism prospects of the Arab Spring countries, “Overall, I’m afraid, it doesn’t seem like tourism there is in a very good position. It could improve in the future but it all comes down to stability. Egypt’s revolution has spiralled out of control, Libya is firmly off the tourist map and Tunisia is probably the safest of the three but even this summer one of their politicians was assassinated”.

Chesshyre says he set out to explore Tunisia, Egypt and Libya to learn about the revolutions and see those countries from a new perspective. “What I took from it most of all was the excitement of the revolution still in the air, and the simultaneous optimism and realism of the people. There was the sense that things could go in two directions.

“I went in a kind of golden period, a year after the revolution, and the feeling was that anything and everything was possible. I snuck through at that perfect moment and had a lot of all of those places to myself, which was wonderful.”

Tom Chesshyre will be speaking at Travel Writing: What Next? at the Henley Literary Festival at 10am on Tuesday 1st October. Tickets are £10 and include coffee, tea and cake. What more could you ask?

For more information about events and authors at the Henley Literary Festival visit the website. And don’t forget to take advantage of the festival’s 2-for-1 ticket offer exclusive to Arbuturian readers. For details, click the link.