In the first part of a special – and epic – feature, The Arbuturian’s inveterate itinerant, Harry Chapman, treads the foothills of the South Tyrol in the company of the world’s greatest living mountaineer…

Lights off, I decided. There was enough coming in from the narrow windows and falling slant ways across the wooden table and rough plasterwork of the interior. I had decided against the high backed chair made of antlers as being a touch on the theatrical side; it might make my interviewee look like Thor.

Lights off, I decided. There was enough coming in from the narrow windows and falling slant ways across the wooden table and rough plasterwork of the interior. I had decided against the high backed chair made of antlers as being a touch on the theatrical side; it might make my interviewee look like Thor.

I glanced out the window at the grey drizzle. There was no denying the location though. I was in Sigmundskron Castle, once home to the Bishops of Trent and the Princes of Tyrol. It was perched on a high crag above the city of Bolzano in the Italian South Tyrol. It was now called the “Messner Mountain Museum Firmian” combining the names of one of the original families with that of the South Tyrol’s most famous son. As suggested by the title, it was now dedicated to all things vertiginous.

I finessed the position of the camera on the table. There was a scrape of a boot at the door. “Herr Messner is ready for you,” said Claudia, one of the PR girls. I nodded. The door swung back and in walked a man who is regarded as not only the greatest mountaineer in the world but who is generally considered the greatest in history – Reinhold Messner.

“Mr Messner – please – have a seat.”

I ushered him over to the chair I had selected which was sturdy and upright – like the man – and I thanked God I had decided against the Asgard throne. Reinhold Messner rarely gives interviews, and never over the phone. I had sixty minutes with him in what is the centrepiece of his new endeavours, the heart of his personal fiefdom. He sat with arms folded and glanced at my video camera. Admittedly it was small and unfortunately the tiny tripod it was balanced on made it resemble a diminutive robot that had climbed up on the table to say hello. For a flash I was in a lost episode of Red Dwarf but then I rallied and my confidence returned. Unshakeable. Small didn’t mean inferior or amateur. It was true I didn’t have the hulking rigs and boom poles of the Italian film crew but everything seemed to be getting smaller these days, from phones to cameras. Small was good.

“Mr Messner, if I could ask you to address your answers to me rather than the camera. Try and forget that it is even there.” He moved his shoulders in the affirmative and drew himself up in his seat. His arms were still crossed. I pressed the record button. The little red light flared into life like a solitary eye. We were rolling.

“One of the things that has surprised and interested me has been the amount of fine art on display in your museums. Can you tell me a little about how this interest started?” I had chucked out all my ‘Newsnight’ style questions digging for a scoop. What I had decided was to begin a conversation and attempt to engage his interest. Adequately softened he might be more likely to let slip a revelation. What was most important though was to keep the flow, to keep all the balls in the air. If he was relaxed what he had to say would undoubtedly be fascinating, and the great thing was, I’d have it all on tape. Well, memory card.

“I have been collecting art and artefacts for a long time. Since the beginning…” he began.

There was a click. We both looked at the camera. The red light was off. I reached down. He hesitated. A flicker of impatience passed across his grizzled features. There was no doubt about it. The camera was dead. Batteries most likely. Poxy things. I could risk his Teutonic scorn and appear a fool by fiddling with it for five minutes but still no guarantees, or I could keep a few shreds of self respect.

“I do beg your pardon,” I piped cheerfully. “There’s no problem. Please, do continue…” Satisfied, he glanced once more at the camera.

“As I said, since the beginning. In Tibet I picked up many treasures…”

I looked from the camera to him, smiled and nodded. The red eye was most resolutely shut. I had no backup dictaphone to record his words, not even a scrap of paper and blunt pencil to jot down the occasional soundbite. I had sixty minutes with the most famous mountaineer of all time and not a single means of recording the experience. He was gathering speed now, approaching full flow when he stopped suddenly. Like a hunter pausing to sniff the air, perhaps he detected some skittishness in me? I leaned forwards earnestly. “Mr Messner, I’m all ears. Even if I miss a word,” I glanced one last time at the camera,”our little friend here will have it all… Ahem… You were saying. About Tibet…”

Crossing South Tyrol: Experience South Tyrol together with Reinhold Messner was how the Südtirol marketing team described this little adventure, for this was not merely one hour with the great man but a full five days. It was a chance to observe at close quarters a living legend, amongst the valleys and peaks of his native South Tyrol and the jagged spires of the Dolomites. It was an opportunity to get close to that most rare of species – a climber who had made it into old age. The access was unprecedented. It was a once in a lifetime opportunity.

When the phone call about the trip first came through I confess I had never heard of Reinhold Messner. My knowledge of mountaineering consisted mainly of knowing that Edmund Hillary was the first to ascend Everest. I wasn’t a climber but I do have a fascination for the remote corners of the earth and for the men that tramp them. There is something mythic about mountaineers or at least the idea of them. It isn’t just the notion of risk and the vicarious thrill this gives, or that the stakes are so high. It is that the reasons for climbing – certainly for climbing at the highest level – are so tantalisingly difficult to define, if they can be defined at all.

“Why did you climb it?” Goes the popular question.

“Because it’s there.” Goes the familiar answer.

Like many others I watched the tragedy of the climbing drama Touching the Void unfold with heart-stopping fascination. A friend of mine – a lady if that makes any difference – remarked to me afterwards, “That film made me so mad. I mean, what an idiot! Why did he go up there in the first place?” And there you have it. The climbing conundrum in a nutshell. There are those that get it and those that patently don’t. And even in ‘getting it’ it is merely the notion of the thing one gets, the beautiful mystery. Climbing is a thing that feeds our dreams and fantasies about ourselves.

If anyone could be said to encapsulate this contradiction, of being both thoughtless fool to some and fearless hero to others, of having scaled the literal heights and of having suffered the most terrible tragedy, of having shown the worst flaws of the climber and also the most brilliant qualities, then that person is undoubtedly Reinhold Messner. His life story reads like fiction, like a film of thrilling impudence (and indeed he has been the subject of several). I am astonished that I don’t know his name, but then, in his most daring and triumphant decade, I was still a boy. For most people in the seventies with access to a radio or television would have been familiar with his various achievements. With his climbing partner Peter Habelar, he was the first person to reach the summit of Everest without oxygen – a feat long thought to be impossible. He was the first person to climb all fourteen “ eight thousanders” (peaks over 8,000 metres, or 20,000 feet) which together make up the highest mountains on earth. If for some his name has faded, in the German-speaking world his is a household name and he is accorded the same status as royalty.

I first met Reinhold Messner in the dining room of the Restaurant Kuppelrain in Castelbello, an alpine village in Eastern South Tyrol. He was standing behind a long table as the thirty-odd journalists from across Europe filed in (a considerable groundswell on the four or five I had been expecting). Like a monarch we were introduced to him one-by-one and one-by-one he flashed his trademark smile, made famous by the numerous pictures of him in mountaineering garb, face blistered by the sun, standing atop yet another conquered peak. As in those it was all gleaming teeth and laughter lines but here it felt reflexive and curiously lacking in warmth. It was only in the eyes that I detected something genuine, a brief lock that suggested Messner had made a lightning appraisal of everyone there. What he thought of me was veiled in those hooded wolf’s eyes.

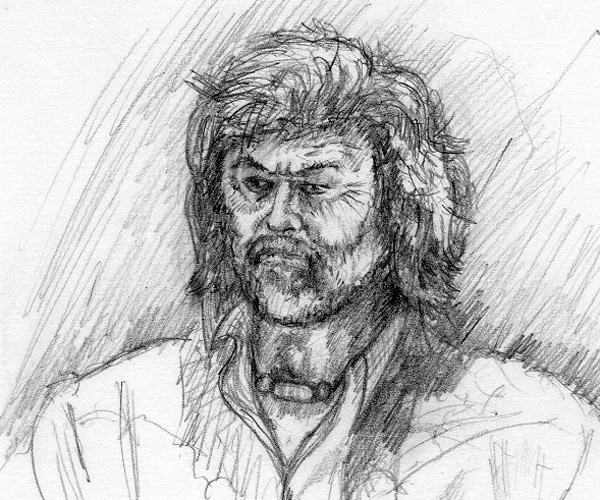

What struck me, even before this, was that for such a giant of the age, he was so comparatively slight of stature. Admittedly I am tall, but when we were both standing he barely breasted my shoulder. As seems often the case, photographs give the lie or at least create an illusion that simply isn’t borne out. Celebrities, at least when it comes down to physicality, are rarely larger than life. Having said that, Messner’s cockade of hair was every bit as preternaturally thick and mountainous as his portraits suggest. Combined with a wiry beard shot with grey, the effect was that of a lion’s mane or one of the more venerable of the Greek gods. He was undeniably a striking presence. But then how could he fail to be, knowing what I did about him, and for the fact that all thirty-four of us were there to see no-one but him?

I was seated at the end of the table and couldn’t hear what he was saying. For this first meal I wasn’t in one of the favoured positions. Behind me, through the open window, the town’s castle perched on a shard of rock; bluff, ochre, but beautiful. It was to be the first of many castles I was to see in the South Tyrol (there are more than eight hundred in the province – the highest concentration anywhere in Europe). Three of the five Mountain Messner Museums we were there to see had been created in castles. The one we were to be taken to the next day, Juval Castle, also happened to be Messner’s private home.