It is amusing when two friends bump into each other, one with a first class ticket and one without and the former turns to the latter and says apologetically but with a note of triumph, “Well, I’d better get a seat so I can go and do some work.” His long face broke into a boyish grin of a hundred lines and he laughed noiselessly for several minutes. He looked like a cross between Dick van Dyke and Roald Dahl – if such a thing were possible – and he was folded into the driver’s seat of the car like a truncated piece of human spaghetti. We were being driven from the station in Haselmere to Midhurst and our temporary host and unlikely taxi driver (who turned out to be a retired surveyor) was giving us the low down on the big town’s principle fauna, many of whom were apparently London financiers.

I can’t possibly comment on Haselmere; we were whisked away from it in a matter of minutes. Midhurst though, our final destination, I got all wrong. It was a place I faintly thought I knew, or knew of. It sounded familiar in the way that certain English place names have a habit of doing. “Mid” – that’s ordinary enough, and “hurst”? Well, there’s Chiselhurst for starters with its chalk caves, then Hurst Green down near my parents in Sussex. Then, of course, there’s the curiously titled Hurstpierpoint College in the same county. I’m sure I’ve encountered a Broadhurst somewhere south of somewhere. Yes, I could see it. Midhurst – a ruined market town in commuter belt Kent, sunk low on the Thames Estuary. And in terms of size – of middling stature as suggested by the ‘mid’ in the name. That was it! Midhurst was an average sized former market town on level ground, once pretty but wrecked by post-war planning, with a centre bisected and circumscribed by numerous ring-roads and outskirts of uniform brick boxes.

I was wrong on every count but one. Midhurst was, or rather is, a market town. And I use the term ‘town’ advisedly but lightly, for Midhurst is little more than a village in size but with the architecture and proliferation of grand town houses which indicate that it was once a place of some importance. And indeed it was. Midhurst, fifty miles from London, was on the road to the important Roman, Saxon and Medieval settlement of Chichester (yes, nowhere near Kent) and being roughly a day’s journey by horseback from the capital, or ‘midway’ between the two cities (and I’ve no idea whether I’ve inadvertently stumbled on the origin of the first part of the town’s name) it was frequently used as a resting point for weary merchants, gentry and even royalty (Elizabeth 1 being one). As I was to gradually discover, the town is stuffed with history, much of it strange and dramatic.

As for being flat, Midhurst is anything but. ‘Hurst’ is Anglo-Saxon for ‘wooded hill’, which is a fair description of the place. The particular one in question here, St. Ann’s Hill, is gloriously wooded and sits to the east of the town, above the sleepily winding River Rother.  Fragments of a twelfth century fortified house are all that is left on the site which once boasted a Norman castle and an Iron Age hill fort (and which was also a centre for pagan worship). More than this, Midhurst resides in an enviable position at the foot of the South Downs which rise to 890 feet at their highest point and is the only bona fide national park in Southern England.

Fragments of a twelfth century fortified house are all that is left on the site which once boasted a Norman castle and an Iron Age hill fort (and which was also a centre for pagan worship). More than this, Midhurst resides in an enviable position at the foot of the South Downs which rise to 890 feet at their highest point and is the only bona fide national park in Southern England.

I had been despatched thither to engage in a weekend of activities including bicycling, canoeing and coarse fishing – I suppose a low form of the toff’s hunting, shooting and fishing. We were all being hosted and nourished for the duration by the splendidly rambling and idiosyncratic Spread Eagle Hotel and were duly deposited there in a huddle of luggage by our splendidly rambling and idiosyncratic driver.

‘Sensitively modernised’ is an expression much bandied about in the literature of historic hotels. They are words aimed at assuaging the doubts of the most gimlet-eyed historico as well as giving comfort to their wives for whom luxury equates scalding water, breathless rooms and chocolates on pillows. It is a term which can mean anything and therefore means nothing. Fortunately it was not an expression I discerned in the bumpf of the Spread Eagle. In my opinion, modernisation is grossly overrated. I am never so happy as when windows rattle, doors don’t fit, death watch beetles hum in the rafters overhead, gale-forced draughts whistle down corridors, piss-pots abound and at the end of the night one finds oneself trading blows with pewter tankards for the last haunch of mutton with a grime besmirched stranger in the snug by the inglenook.

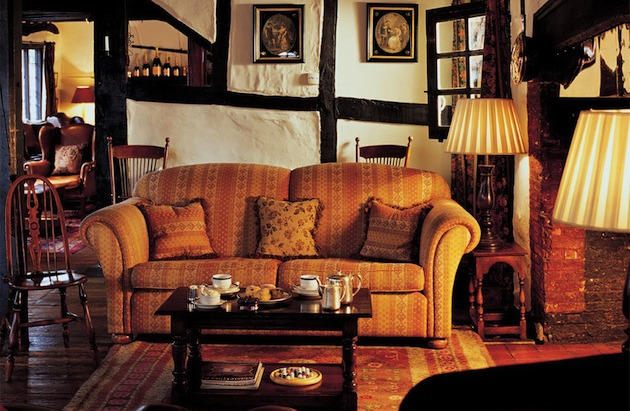

I might add that none of the above were features of the Spread Eagle but in the inn’s six hundred years of venerable history, they may well have been. In fact with its bricked up archways, low rafters and dark oak panelling, its long passageways, working inglenooks and a pleasing hodgepodge of architectural contributions ranging from the fourteenth century to the present, it took little imagination to picture Elizabeth 1 sweeping along a corridor in ermine-trimmed cloak followed by her retinue, or Guy Fawkes in hunched and murmured conversation by the chimney stack, Edward V11 wandering through with a brace of partridge, HG Wells dreaming up future stories as a pupil at Midhurst Grammar School, and most bizarrely of all, Herman Goering stopping off for a pint of porter between watching the races at Goodwood and house hunting for an English country seat. As one of the oldest coaching inns in the country, the Spread Eagle has had more than its fair share of the glamorous and the notorious.

All the rooms are individually named, either after historical occurrences or after famous Sussex personages. The Queen’s Room is reputedly where ‘Good Queen Bess’ stayed and the curious ‘wig closet’ there, perhaps the last in a hotel in England, may well have housed one of her tonsorial appendages. Then there is the White Room with its secret portal leading to a smuggler’s passage. I myself was billeted in the Hilaire Belloc suite which was through the ancient sitting room with its heavy beams and broad floor boards and up a rickety staircase at the back. I believe the HG Wells suite was across the way. This was either purely coincidental on the part of the owners or playfully irreverent; the staunchly Catholic Belloc, a contemporary of Wells’s and like him a Sussex immigrant, had a public spat with his Unitarian peer for what he considered his secularist views.

All the rooms are individually named, either after historical occurrences or after famous Sussex personages. The Queen’s Room is reputedly where ‘Good Queen Bess’ stayed and the curious ‘wig closet’ there, perhaps the last in a hotel in England, may well have housed one of her tonsorial appendages. Then there is the White Room with its secret portal leading to a smuggler’s passage. I myself was billeted in the Hilaire Belloc suite which was through the ancient sitting room with its heavy beams and broad floor boards and up a rickety staircase at the back. I believe the HG Wells suite was across the way. This was either purely coincidental on the part of the owners or playfully irreverent; the staunchly Catholic Belloc, a contemporary of Wells’s and like him a Sussex immigrant, had a public spat with his Unitarian peer for what he considered his secularist views.

Unusually perhaps for a place so ancient, so preserved and so seemingly moderate in size on first view, the Spread Eagle also boasts a spa and indoor swimming pool. When I say the two have been “sensitively incorporated”, I do so without guile or irony. The building housing them has indeed been stitched into the fabric of the place with becoming nous.

I repaired to the swimming pool for a pre-dinner constitutional to try and knock my appetite into shape, if such a thing were ever needed. The pool, although on the small size, was just about big enough for laps but I doubt if it was ever used for such – elegant turtle glidings and peaceful rotations on the back were more the order of the day. Soon my propulsions had washed a couple of elderly dowagers into the shallows where they bobbed against the steps like untethered life buoys. The rest of the occupants, reclining on sun loungers in white towelling robes like occupants at a sanatorium, watched me over their copies of Country Life and Harper’s Bazaar with a mixture of alarm and bewilderment.

There were six of us at dinner which was held in the Queen’s Room, a beautiful private panelled dining room with a fireplace and large sash windows fronting both the street and the lobby, which I believe had been part of a private Georgian house before the old Medieval inn had extended its grip and swallowed the surrounding properties. The evening was hosted by Ted James, the dapper manager of the establishment. A country sort with a military bearing, Ted’s somewhat formal appearance belied the great natured heart of an epicurean. As the meal progressed and we were treated to food that was locally sourced including sparkling wine from Ridgeview, crab and lobster from Selsey, lamb from Ditchling and game from the Balcombe estate, he revealed a wicked sense of humour and a laugh as high pitched and infectious as a naughty schoolboy’s.

By eleven I was feeling distinctly torpid. The wreckage of a very fine meal was strewn before us on the white tablecloth. I declined further drinks at the bar as being the wisest thing. There was a glint in Ted’s eye which promised no return. Instead I made my way back to my room.

In the middle of the night I was visited by nature’s call. Slipping out of bed to use the facilities I staggered and almost fell. Clutching onto an oaken beam I steadied myself like a novice sailor on the deck of a galleon. It was odd. I had drunk ‘to be social’, as the saying goes, but not to excess. Unless these southern county wines were of unparalleled potency or Ted had mischievously enhanced their value, I couldn’t work it out. I continued on my groping course and returned to bed as though it were a life raft.

In the morning all became clear. It wasn’t me that was bent out of shape, but the room. The ancient timbers of the chamber, assisted by the shifting earth, had created a sort of internal adverse camber reminiscent of a ship’s deck on a downward slide. I don’t know how straight the floor in HG Wells’s suite was but I imagine Belloc’s dubious slant must have brought a smile to his old adversary’s lips, wherever he was in the cosmos.

Nigel Greenwood’s arrival in the breakfast room reminded us that there would be more to the weekend than scoffing country fare, scaring septuagenarians in the swimming pool and lolling about on large beds under fifteenth century rafters. Together with his Swedish wife Maria, he ran the Sussex-based outdoor activities company So Sussex which specialised in a variety of things al fresco including canoeing, hiking, mountain biking, fishing and mushrooming. Grizzled and cropped of hair, he was accompanied by Allan, another member of the team. Both had the ruddy complexions and shiny wind tans of the true outdoorsman.

Nigel Greenwood’s arrival in the breakfast room reminded us that there would be more to the weekend than scoffing country fare, scaring septuagenarians in the swimming pool and lolling about on large beds under fifteenth century rafters. Together with his Swedish wife Maria, he ran the Sussex-based outdoor activities company So Sussex which specialised in a variety of things al fresco including canoeing, hiking, mountain biking, fishing and mushrooming. Grizzled and cropped of hair, he was accompanied by Allan, another member of the team. Both had the ruddy complexions and shiny wind tans of the true outdoorsman.

Wearing fleece liners and a profusion of Velcro straps they were also both decked out in the most up to date of off-road cycling garb. I had always considered the cycling fraternity’s obsession with lycra and artificial fibres something of an aberration. Unless you were putting in serious mileage ordinary clothes would perfectly suffice. Ever since I heard the acronym MAMIL (middle aged man in lycra) on the eve of my fortieth birthday, I had been haunted by the term. Still the boys didn’t look like they did things for show. I glanced down at my thin shorts and cotton shirt with a moment’s doubt.

As soon as we pushed out of the stony parking lot on our mountain bikes we were met head-on with a freezing northerly breeze. Although late April and the sky held flashes of blue, it was cool and the high hedgerows formed a cruel wind tunnel. And this was low country. I dreaded to think of what it felt like at the top of the Downs. Which was exactly where we were going.

But this was beautiful country, too. The recent rain had drenched the earth and when the sun came out the green turf of the fields shone with an emerald brilliance. We had also turned off the high road and slid along gently rolling and empty lanes at right angles to the wind. The hedges now provided a protective lee. The Downs rose dramatically to our left and their proximity gave us an instant sense of our puny human scale.

Without warning Nigel turned off the asphalt road onto an earthen track. White chalk and sharp flint, this was one of the typical Sussex drover’s paths which bisected the hills, leading from the sheltered valleys to the exposed uplands. Meant for cart wheels and cloven hooves, it was now just about negotiable by four-wheeled drive – and bike.

The incline was sudden, and shocking. Within moments I was in my lowest gear and high in my saddle. Even so the ascent was barely more than walking pace. The track was deeply rutted and strewn with hunks of flint that threatened to rip a tyre in two if caught at the wrong angle. Occasionally my bike would slip into one of the troughs and movement would cease altogether – I would be frozen in mid-revolution, one foot high on a pedal, the other one low – until the mechanism of the thing grudgingly ground round and the steed would jerk into life.

I pulled away from the others, not out of braggadocio, but to stop, even for a moment, meant keeling over. There was no choice but to pedal, and to pedal hard, or to walk the bike up. There was another advantage to all the hard work. For the first time in the outing I was actually warming up. Finally I reached the top and was soon joined by Allan. We waited under an oak tree bent double by the prevailing wind like an old man bowed by a sack of belongings, and chatted, discovering a common bond in our love of wild places wherever they might be and a desire to fling ourselves into them by foot or bike or boat.

Soon we were off again, bouncing along the crest of the hills on the hundred mile South Downs Way which runs from Eastbourne in the east to Winchester in the west. I knew the route well, having traversed it first by bike, then by foot, some years before. It was unchanged apart from in the season and the weather, which are forever changing. These hills (and “downs” is from the Old English “dün”, meaning hill) were like old friends.

This now was easy riding, a chance to lean back, breathe in and enjoy the views, which were tremendous. These were some of the highest natural points in all of Southern England. To the south the shimmering sky met the horizon over hills which dipped and rose like the sensuous curves of a reclining nude. Just visible between them, glittering like a mirage, lay the sea. To the north, stretching away beneath the steep chalk escarpments and wooded drops, all of Sussex lay spread out like the proverbial patchwork quilt, ruched here, rolling there, a picture of meadows, sown fields, copses, villages and snaking rivers. The blue haze of morning hung over Surrey and obliterated London as though the smog filled capital ceased to exist.

After a few miles we turned north down a side path and, bombing down a steep decline, found ourselves miraculously back at the car park and the waiting jeep and trailer. We returned to the “Spread Eagle” where we fortified ourselves with sandwiches and fruit from the kitchen and I welcomed my wife and baby daughter who had come for the night, before we set off for the second part of the adventure – canoeing up the River Arun.

There was a pub above the muddy slip where Nigel and Allan dragged in the canoes, which is always pleasing, whether you avail yourselves of the taps or not, and we most certainly did. Here we were joined by Ollie, one of the newer members of the team, who was to be our river guide for the afternoon. Dark haired, swarthy and stocky with a gleam of life in his eyes, he had worked as a professional white water guide all over the world before returning to England with his wife to raise a family. It was clear that water, rafts and canoes were still his thing though.

In pairs we took it in turns to step into a canoe and disappear up the river with our veteran guide. Those of us not engaged would sit on a bench in the sun with the rest of the crew under the ancient willows which fringed the bank. Above us a noble brick and stone arched bridge, too narrow and aged for the traffic that now raced by on the new concrete span thrown higher up, completed a picture of quiet English rusticity.

I was last but eventually my turn came and being last there was more chance to savour it. We stepped into the flat bottom of the gently rocking canoe and gripped the gunwales. Ollie hopped in lightly and pushed us off. It was a Canadian canoe, curved slightly fore and aft like a half-submerged banana and open to the elements. This one was a bulky old thing with enough space amongst the cross planks for some serious storage. I had canoed a reasonable amount over the years and knew one end of a paddle from the other. Paddling was straightforward enough. The difficulty was keeping rhythm with your partner – especially if you hadn’t paddled together before – so that the boat went in a straight line and at a decent rate. To this end Ollie sat in the stern with a short steering paddle in his hands.

Within a few strokes we had rounded a bend and the others were out of sight. Their voices were cut too suddenly – sliced away – occasionally reaching us on snatches of open space as short singsong melodies. Within a few more strokes even these had died. The pub and bridge had gone. We were in deep countryside, as low as the Downs were high, the only sounds the dip and swish of the paddle, the occasional clunk as one knocked against the side of the boat, and the thin hiss of the prow as it cut through the water. It felt so remote – it was difficult to believe that there was human life a mere quarter of a mile away. High on the Downs you had everything spread before you. One surveyed the world like an eagle or a general. Here the view was narrowed, truncated. You didn’t look out but up. Here you needed imagination.

The sky was a light Spring blue now and the sun warmed our backs. The wind had dropped entirely. It was so still. The river was sunk below high banks and because it was so narrow here one was denied the knowledge of the immediate terrain which was both frustrating and tantalising. One caught glimpses of grassy levels and wooded rises. What else was there? It felt so peaceful but the detritus that hung on the high branches of overhanging trees reminded us of how violent things might get when the river was in spate. We lowered our voices out of respect but even these murmurs clanged and sounded out of place. Ollie raised a hand and we drew in our paddles and drifted. Gradually what seemed like deep silence became honeycombed with sounds which wafted in from near and afar – the lowing of a cow, the tremulous whistling of a tit, a scratching in the undergrowth of the bank. He pointed to the sky overhead. Two buzzards wheeled elegantly in the updrafts. A pheasant broke cover, charged away from the bank and flapped clumsily into the air like an avian version of one of those ungainly old military planes.

We returned reluctantly to our waiting friends. It had only been half an hour but in the expansiveness of the experience it felt much longer. I could have happily stayed out there for hours, drifting and paddling.

Harry’s Sussex sojourn concludes tomorrow…

The Spread Eagle Hotel & Spa is one of the Sussex Historic Hotels. For more information and rates, click here.

For more information about outdoor activities and suchlike in Sussex, visit the So Sussex website.