It was now time for the third and final of the day’s adventures. Although the idea of fishing had long appealed, I confess I had never cast or dangled a line. I knew that there were many varieties of fishing suiting different pockets and breeds, that a sort of hierarchy existed and along with it a degree of snobbery, inescapable perhaps in a country with such a long love affair with class, but odd all the same in an activity so seemingly natural and noble. The fly fishers looked down on the coarse fishers. I’m sure the reverse was true.

My grandfather had been a fisherman but I knew this only by tale and photograph. My only direct experience of it was my mother’s attempts on the east coast of Australia when we lived there back in the eighties. The bait were a species of shellfish which lived under the wet sand on the shoreline. We kept them in pots of saltwater in the bathroom. In the morning their shells opened a crack and they sent forth peeping eyes on long stalks to investigate this strange new environment. Whilst in the short space that I knew them they didn’t exactly become pets, they did develop character (certainly as much as some of the teachers at school). Despatching them therefore was a sorry business and I kept well away. On the line they were either lost or were pinched by the prey. The only time my mother ever caught a fish, in a rather harried state she kept it in a bucket of seawater overnight before returning it to the sea the next day. She never picked up a rod again.

Still, it seemed to me that the ultimate purpose of catching a fish must be to eat it. Releasing it afterwards always struck me as rendering the whole operation a trifle, pointless. Yet in coarse fishing that is precisely what you do. And that day we were going coarse fishing.

The lake we were using was created for the purpose. As such it was a curious shape with long adjoining legs and little abutments, I suppose to maximise the vantage points for fishermen as well as to provide a variety of shelter and habitat for the fish. Despite its amoebic shape it was an attractive place with enough reed and tree cover on the banks to give it character. The water, although muddy, looked fresh and clean. As a wild swimmer I would rather have been in it than gazing upon it though I don’t know how smoothly this would have gone down with the piscatory committee.

Fishing was Nigel’s domain. He had been practising since he was a boy and clearly it was a passion which had increased with age. The first thing was selecting a spot, which wasn’t as straightforward as it sounds. Everything affects the disposition of the fish from cloud cover and the direction of the wind, to water temperature and the position of shade thrown by overhanging branches. Fish respond differently to different conditions and different species respond differently to each other. A good fisherman understands these things. He doesn’t cast a line and expect the fish to come to him, he reads the signs and goes to where the fish are. None of us there had any real experience of this ancient of practices. We were to discover that it was as much science as art – more, it was a philosophy too.

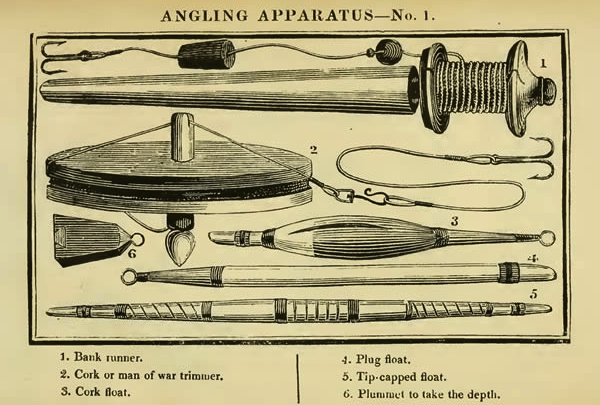

Whilst the basic tenets of fishing have remained unchanged, there have been considerable advances in equipment since my mother waved a rod at the ocean. For “sporting” fishermen – that is, those that release their catch – the hook is now a much more refined instrument with a barb that is smaller and retractable and so minimizes damage to the fish, particularly on extraction. Bait is the other thing. The live stuff is still available and of course there is nothing stopping an angler grubbing for worms and other creepy crawlies, but the artificial bait now on the market is apparently every bit as alluring to a fish as a wriggling grub or beetle. Fortunately this is what we were provided with and so were not obliged to impale a maggot. The bait was small, bluey-green and rubbery, resembling little balls of rolled up blu-tac, and took some finessing to get on the end of the hook.

The lake was home to carp, perch, roach, rudd, bream and possibly the odd pike we were told. Nigel selected a medium sized hook to give us a wider span of prey and so increase the odds. No one was going to land a whopper but we were promised that each one of us would catch something. Cynical me considered this pledge a trifle optimistic.

One by one we took a seat on an upturned crate on the bank by the water’s edge. A handful of bait of another type was scattered in the water – a sort of appetizer to lure the fish in – and the line was cast. Ranged round in a silent group broken by the occasional murmured instruction from Nigel, we did what much of angling consists of – waiting – watching the bobbing float with eagle eyes.

Sure enough, as promised, the float quivered, there was a tug on the line and each novice fisherman swayingly but triumphantly drew in their prize. Admittedly none of them would have broken the scales, but did it matter? These were real live fish bamboozled onto a line and coaxed in with panache. Photographs were taken and the gasping fish was returned to its watery world.

As usual I was last. I took a seat and balanced the rod in my hands. I had a growing presentiment that the fish had realised what was going on. They had wised up. Would I be the only one in the group who would fail at his piscatory endeavours?

As usual I was last. I took a seat and balanced the rod in my hands. I had a growing presentiment that the fish had realised what was going on. They had wised up. Would I be the only one in the group who would fail at his piscatory endeavours?

Suddenly the line went taut. Like a faithful but unobtrusive co-pilot Nigel steered me home through whispered instruction, “Left a bit, right a bit, easy now.”

Slowly I reeled in the monster, the rod bowing to its weight. I steered it into the bank and a keep net was drawn in under it. Up it came – a flapping silver bream…of at least four inches in length!

The day was over. In a flush of victory we returned to the hotel and I celebrated my triumph with a quiet early evening swim. Showered and freshened up I met my wife in the restaurant where a final group meal was laid on. Alas Ted James was not present to entertain us but the meal was every bit as good as the night before – better, probably, given our exertions. That night I slept like a log.

Our time was nearly up but there was one thing left in the town that I really wanted to do. I have always been a fan of castles – ruined or intact, rambling or compact, follies or the real thing – and I discovered that Midhurst had a fine one with a rich, bizarre and ultimately tragic history. Combining my curiosity with a good deed, I left my wife to slumber and scooping up my wide-awake daughter, stepped out of the Spread Eagle at seven o’clock.

It was Sunday morning and Midhurst too was asleep. It was a beautiful Spring day and the sun flung its low rays across the roofs of the town, setting the red wonky clay tiles ablaze. The castle was about half a mile distant and we wound our way through the narrow streets of half-timbered, white washed and ancient hand-cast brick houses before emerging on the gentle slope of Rumbolds Hill. To the right a vast flood plain stretched out to the west of the River Rother. Bisecting it at a diagonal, as straight as a Roman road, lay an impressive causeway. At its furthest end, across the river, lay the castle.

Cowdray House, as the name suggests, is not really a castle in the strictest sense. It was built a hundred years after the era of castle building had come to an end, when the idea of state had replaced the chain of loyalties which represented the feudal system. Still, the then owners, The Viscounts Montague, couldn’t resist the allure, romance and perhaps sense of power of an earlier age and the house, or what is left of it, is festooned with battlements, towers and other martial features. None of this would have been designed to withstand a siege. This was a Tudor mansion and the stern stone façade would have concealed a network of rooms and halls that represented state of the art living for the time. After all, as prominent members of the court the Montagues were expected to entertain on a lavish scale. Henry VIII and Elizabeth I both stayed at the estate.

Daisy and I crept along the causeway toward the castle gates. It was an approach that was obviously designed to strike maximum awe into friend and foe alike. Even now, in ruins, the castle was a magnificent sight. The rising sun fringed it in a halo of gold, like the crown of some beatified king, casting the whole in sharp silhouette, notching the crenellations in black and the great mullioned windows, now devoid of glass, gaping like huge blind eyes.

We crossed over the river and through a wooden gate and were confronted by a large set of black wrought iron gates shackled by a chain and padlock set into an encircling wall. The property was in the care of the Cowdray Estate and at this hour was still firmly shut up. We skirted the wall. I was looking for a way in, a scaleable point of egress with a not-quite-two-year-old child. And very soon we found one – a low, broad ruined brick wall which I quickly shoved the baby onto whilst I shinned up using the vertical iron bars on an abutting piece. We must have looked an unlikely pair of trespassers, Daisy in voluminous pantaloons and a pink cardigan and me even more improbably dressed in tweed plus fours, tweed jacket and flat cap. But it seemed a shame to get all the way down there without stealing a proper look.

And so we wandered at our leisure my accomplice and I, through the open arch of the gatehouse, over the remains of the beer cellars, past where the massive regal staircase would have once stood, imagining life as it may have been. Fireplaces sat one atop the other as the storeys rose, as though we were granted a real-life anatomical cross-section from the architect’s plans.

With the sun beginning to climb and the birds twittering in the woods, it was difficult to believe that the house and its owners had been subject to a curse, but so the story goes. For the Montagues owed their great wealth to the Dissolution of the Monasteries and according to family legend, a monk turned out of Battle Abbey which had been seized by a relative, prophesied that, “By fire and water thy (the Montague) line shall come to an end, and it shall perish out of the land.”

Ironically the family continued as Catholics although a connection with Guy Fawkes, who was employed for a time in the household, landed the 2nd Viscount Montague in the Tower of London for forty weeks on suspicion of being involved in the Gunpowder Plot. A second blow to family prestige came during the Civil War when the house was captured by the Parliamentarians and converted temporarily into a barracks. It wasn’t until 1793 though that the so-called “Cowdray Curse” really became manifest, and in a stunningly dramatic way. In that year the house was devastated by fire and the 8th Viscount Montague was drowned in the Rhine. In 1815 the Curse was fulfilled when the last two sons of the Montague dynasty were drowned in a boating accident.

The house was never re-built. It is now in the possession of the 4th Viscount Cowdray of a new line of viscounts and no descendant of the original. As the current Viscount dwells in the stately Cowdray Park nearby which also houses the Cowdray Park Polo Club, one of the leading clubs in the country, it can be conjectured that the curse has not been transferred.

We wandered back along the peaceful River Rother, passing the ruins of even earlier fortifications on St Ann’s Hill before breakfasting like kings back at the Spread Eagle. I exchanged my “foot and leg energiser” for a back massage at the spa and a very fine back massage it was too. And then we were away, whisked back to Haselmere with curses, castles, fish, rods, canoes, bicycles, rivers, hills, feasting and plotting all vying in my mind for primacy. In a word – history – both natural and human. That’s Midhurst.

The Spread Eagle Hotel & Spa is one of the Sussex Historic Hotels. For more information and rates, click here.

For more information about Cowdray House and the Cowdray Heritage Trust, visit the website.